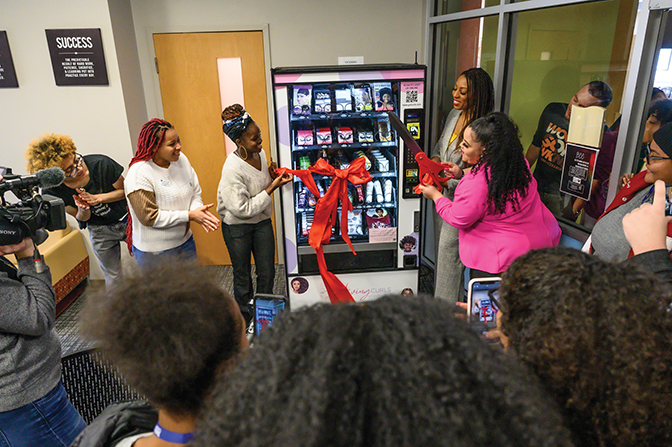

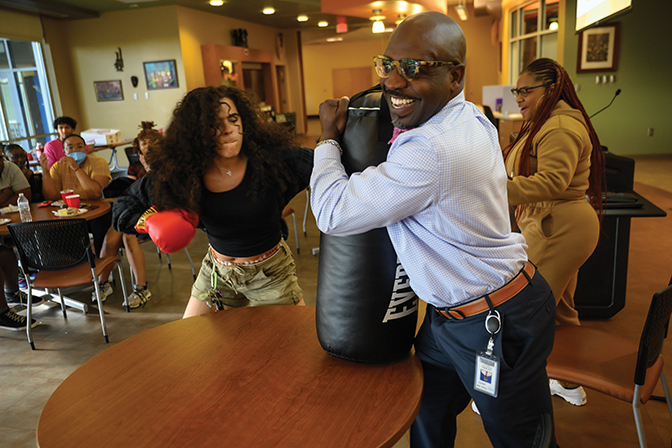

It’s a Saturday afternoon, and the main room of the Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education is abuzz with people of color but with a diversity of age and gender among them, and some curious local media trying to tell the story in their own ways. In the back of the room, Joel Wilson ’02 is cutting hair as part of the Chop It Up program, a kind of on-campus barber shop he developed for students of color. And soon in the adjoining Black Cultural Center, the ribbon will be cut for the inaugural opening of a beauty-care product vending machine for Black students—the first of its kind in Kentucky.

Entering this space as a white man tasked with telling a story about people of color and their hair, I decided to approach the issue cautiously because it was new territory for me. This story was an opportunity for me to learn, and while it might seem odd that I be the one to report on it, something about it also fit right in with the vibe and purpose of Berea College: that Bereans with different identities can come together and appreciate their common humanity.

As I walked around the event, I approached the vending machine containing a plethora of products that addressed the care of hair, skin, nails and even eyelashes. A kind woman nearby explained two things: that it was hard and expensive for young women of color at Berea to travel to Lexington, where the nearest salons were with stylists who understood different textures of hair; and that many of the products in the machine could not be found in local stores and were cost-prohibitive online. She also explained the importance of the use of satin materials because of the way it interacted with kinky or coily hair.

The Vending Machine

The haircare vending machine installed at Berea was the brainchild of Melanie Day, curly-hair and hair-loss specialist, consultant and owner of You’ve Got Curls and Hair Loss Center in Lexington, Ky. A native Lexingtonian, Day grew up in an entrepreneurial family that quickly understood she had a passion and talent for haircare and encouraged her to pursue it as a career.

“I started beauty school when I was 17,” said Day, who noted that there wasn’t much in the curriculum at that time about different textures of hair. “I didn’t want to be stuck just doing one type of hair. I have friends from all over the world. That’s where my love for all textures of hair really started.”

So, Day made hair textures her main focus and, in addition to what she was learning at beauty school, she began networking with other stylists to make up for what the school couldn’t teach her. Eventually, she had her own shop where she applied her special knowledge.

“I’ve had quite a few clients who are either current Berea students or graduated from Berea over the years,” Day related, explaining how far they had to travel to see her, but also the diversity of students who came. There were young women of color, certainly, but also young white men with their own kind of curly hair who wanted to know how to manage it.

“It’s experiences like that,” Day continued, “where the community comes in. You can have differences, whether it’s physical, political, ideological, whatever, but you can have a bond over your hair.”

Day sympathized with the distance Berea College students were traveling, some even up to northern Kentucky, and the problem sparked an idea to bring her salon to campus through the haircare vending machine. Certain trade secrets prevented her from describing how it went from idea to reality, but the celebratory unveiling of the machine on campus helped Day realize something else about it.

“This is bigger than hair,” she said, “because oftentimes you’re told you’re not good enough or your hair is unprofessional. It’s a big deal to have products for your hair and skin so you can look good and feel good about yourself. It’s bigger than hair—it’s to be seen.”

While Day brings a vending machine to campus, the campus is bringing students to her salon for internships. There, they learn how small businesses work by doing cost comparisons and price adjustments, along with public relations and social media management. But also, they’re being seen.

The Barber Shop as Sanctuary

Joel Wilson matriculated at Berea more than 20 years ago; he was recruited by Darlene Lattimore-Cartwright ’87, who was brought to Berea by Virgil Burnside ’74, retired vice president for student life. Wilson earned other degrees after he graduated from Berea and, just before coming back, worked in nearby Richmond as a mental health therapist for people suffering from opioid addiction. Fate and past connections brought Wilson back to Berea in 2019 to work as a psychotherapist in the College’s Counseling Services. His job description, though, had an interesting twist: find new ways to extend counseling services to historically underrepresented students, especially students of color.

“One of the things I observed that hadn’t really changed much was that students still had hair, and people still needed haircuts. And they still didn’t have barber shops in the area.”

Wilson remembered his own experience at Berea, where he had to cut his own hair, a practice he’d incorporated since moving to Kentucky when he was 14. By sophomore year at Berea, he had become a barber for other young men and has been cutting hair ever since.

“So, there is a phrase a lot of people use in the communities I’m connected to,” Wilson said, “when we’re sitting down and talking or processing things that I just kept hearing: let’s chop it up; let’s sit down and talk.”

In the process, Wilson discovered a bridge between cutting hair and getting students to talk about things. “That’s how it got started,” he said, “a place students can come and talk, so you’re literally chopping hair and chopping up issues.”

Then Wilson connected the mundane setting of the barber shop to another place that transcends racial and ethnic categories: the sanctuary.

“The idea of a sanctuary,” he continued, “is that something spiritual is happening; a person can come in and feel seen and appreciated just as they are.”

His imagery also has to do with uncles and father figures. He grew up in two places, in Cincinnati, where he could find a sort of uncle at a barber shop on any given day to get a haircut; then he moved to Kentucky and lost that connection because the barber shops in his new place involved white men cutting white men’s hair. They were older men, chopping it up in their own way, talking about the daily news or what was going on in town.

Wilson talked about barber shop “shenanigans” and good times, but also conversations about serious matters of the heart and young men being in a space with older men and the intimate, vulnerable outcroppings of missed opportunities that these father-figure relationships fill in, like learning to tie a tie, how to treat a lady or how to shave.

“That is a counseling session in its own way,” he said. “It’s very sacred because everybody wants to be seen, and sometimes we might go about it in a dysfunctional way, but in that setting, you don’t have to do that—you’re literally shedding hair, and you’re literally shedding parts of yourself.”

In the United States, the experiences of people of color are harder in many ways, but also when it comes to hair. Across the nation’s tense history, Black people especially looked for ways to straighten their hair or use chemicals to better conform to white culture in order to survive or just find a job. This creates a psychologically damaging “double consciousness,” in Wilson’s words, where people must hide away important parts of themselves and in the process of self-denial create an inner world of unpacked trauma. “Ultimately,” he said, “the true trauma is when we have to betray the truth we know about ourselves in our situation.” The barber shop becomes a therapeutic sanctuary for releasing and resolving these tensions.

So, when it comes to people of color and trying to change their hair, he explained, the process not only denies a sense of self-worth, but it manifests into the world as disbelief in the future self: With my tightly coiled or loosely coiled or biracial hair, will I be called back for an interview? Do I have what it takes, just being me, to become CEO or senator?

Wilson also wanted to highlight one other thing: a student, young, white and Appalachian, told him he wanted a haircut and wanted it done at Chop It Up despite being able to go anywhere in town, but he didn’t want to take a space away from his peers of color. Wilson told him that no matter what, there would be a space for him because this is Berea, and everybody deserves to be seen.

Crowns and Black Girl Magic

It was Kristina Gamble, director of Berea College’s Black Cultural Center and an Appalachian person of color, who made the deal with Day to bring the haircare and beauty product vending machine to campus, an arrangement that also included the participation of Campus Life. Gamble expressed how the home kitchen, instead of the barber shop, is a kind of sanctuary as well, where women of color, as sisters, gather for several hours at a time and do each other’s hair and talk about issues. On campus, so far away from salons and stores with the right products, the home kitchen has taken shape in residence hall spaces, where the same things go on.

When it comes to the hair itself, Gamble uses the image of a crown.

“For Black women,” she said, “our hair represents our crowns. Being Black is not a monolith. Our crowns come in different shapes, sizes, textures, curl patterns and hues. Our crowns deserve care as they represent strength and self-love on a spiritual level.

“Getting our hair done collectively and collaboratively represents sisterhood and a way to build community,” she continued. “It’s not uncommon for us to spend three hours or more caring for our hair. Many hairstyles, like braiding, can take four (hours)—even longer to complete. This provides plenty of time for conversation. It doesn’t matter your background, age, career or socioeconomic status. You’re just able to participate in dialogue sister to sister. We talk about our hair, of course, relationships, dreams and goals—a beautiful experience filled with laughter, advice, pride, wisdom and love that sums up what is affectionately known as Black Girl Magic.”

Gamble reiterated how excited she was to be able to provide Berea students with accessible and affordable haircare solutions on campus and how long overdue it was. She hopes other institutions across the country will follow Berea’s example. And so do I.