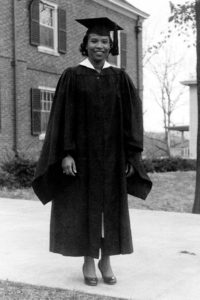

Jessie Reasor Zander’s name appears along the campus sidewalk on one of many banners honoring notable Berea alumni. Say the name out loud on campus, and the likely refrain is as follows: Jessie Zander was the first African American to graduate after the segregationist Day Law was set aside.

Chances are, though, not much else will be said. Such is the case with certain names. John Fenn won the Nobel Prize. Sam Hurst invented a kind of touch screen technology. For Jessie Zander, there is more to her story than that, and we aim to tell some of it.

(Photo: Berea College Special Collections and Archives)

Graduating in 1954, Zander took her place at an integrated commencement, the likes of which Berea hadn’t seen in 50 years. The 1904 “Day Law”

is infamous in Berean lore. It was the state legislation that segregated private colleges in Kentucky, an action taken in direct response to Berea’s founding commitment to interracial education. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately sided with the State of Kentucky in 1908, and Berea College would not admit another student of color until Zander became one of a small number that matriculated in 1951.

Previously, Zander attended Swift Memorial Junior College, a Presbyterian school for African Americans in Rogersville, Tenn., about 60 miles from her childhood home in Appalachia, Va., where segregation was an unfortunate fact of life. Zander describes the time period as having a sharp line between races that wasn’t crossed.

“You didn’t question it,” she said. “You didn’t know that there would ever be a change in it.”

Zander’s family moved to Virginia from Alabama to seek work in the coal mines and with the railroads, a step up from working as a domestic in people’s homes in the Deep South. They lived among a row of homes built for black families, with property ownership enabled by her grandmother, Cherrie.

“I observed her continuing on regardless, a fifth-grade educated woman out of Alabama, who didn’t rant and rave about her position or what was occurring, who used her wits and bought land or assisted her children in buying land,” Zander said.

[pullquote cite=”Jessie Zander ’54” type=”left, right”]Keep moving forward. Connect to people who can assist you. There’s always a way.[/pullquote]

Separated from her mother at a young age, Zander was reared by Cherrie, who instilled in her the importance of education early on. Zander recalls “a beautiful, smiling, dark-skinned woman” who prayed her granddaughter would be educated despite the lack of financial resources to make it happen. To implant the idea permanently in her granddaughter’s mind, Cherrie kept the phrase “now, when you to go to school…” in regular use.

At the little Baptist church nearby, Zander considered her grandmother’s admonitions as she developed her talents.

“I learned to be who I am today by going to the church on the end of my street,” she said. “I learned about how to work with people in that little church. I learned in that little church how to get up in front of a group and speak and sing and work with children younger than I.”

It was amidst this backdrop that she overheard her Sunday school instructor tell Cherrie that Jessie would make a fine teacher. Zander recalls, too, that it seemed the only career options for African-American women at the time were teaching or nursing. Because of influential teachers in her life, she was inclined toward education. What remained was finding an answer to her grandmother’s prayers of school for her granddaughter.

One day at Swift Memorial, a recruiter from Berea College visited Zander’s class and told them about the school. “I was quite surprised such a place existed,” she said. “That motto of Berea is very strong: God has made of one blood all peoples of the earth.”

Her religious background allowed her to absorb the words and note that though people expressed a belief in equality, they did not behave as though they did. “It was already in place in my heart and mind, the equality of people, even though I wasn’t experiencing that.”

The recruiter asked the students to raise their hands if they were interested in attending. Zander was the only student to do so.

Until Berea, Zander had never attended classes with white students. She often found herself the only African American in her classes.

“Not having had close interaction [with white people], I felt like a fish out of water,” Zander said. “I was welcomed by people, treated kindly, but it took time, both for me as an African-American student and for whites who had not lived with African Americans. So we were wary, but kind enough.”

Though wary, Zander says the overall experience of being surrounded by people interested in interracial living was positive. Also, it was good experience for her future career as a principal of integrated schools.

“I could not have done these jobs in Arizona (where she now lives) where I was in a large minority if I had not had that experience,” she said.

Still Committed

Interracial education is Berea’s fifth Great Commitment. (Explore the Great Commitments.) That commitment requires a community characterized by diversity and inclusion. Earlier, diversity in our country and region primarily centered around the black/white divide. Now that historical commitment is foundational for building community among “all peoples of the earth,” so that Berea’s inclusive community includes persons of all the major ethnicities in our country and international students as well. Learn more about diversity and inclusion.

[/content_band]

The road to becoming a principal, though, was bumpy. Outside of the College, 1950s Kentucky was not a welcoming place. When it came time to do her student-teaching, she was presented an opportunity to work at a nearby school with other future teachers. However, she had a hunch that because she had not met the principal who hired her in person, he may lose interest once he discovered her race. Zander called to inform him and ask if the job was still hers.

“The person said no; they did not wish to have me,” Zander recalled. “I was disappointed because I would have wanted to go with the ones who were going to have this experience. It probably would have been a very different experience from teaching in a black school.”

Her Berea mentor, Dr. Robert Menefee, made sure to let that principal know his school missed out on a fine young teacher. Through some other African American connections, Zander completed her student-teaching at Middletown School in Berea, a school for black children.

(Photo: Jasmine Towne ’16)

Thus was the beginning of her teaching career. Eventually, Zander landed in Arizona, where racial tensions continued, especially as attempts at integration meant busing in students of color from their neighborhoods to be educated alongside white children.

Zander, who presided over these tensions as principal, believes many of the teachers were not trained well enough on how to handle the new situation. She tells stories of inappropriate, racially tinged gifts and of teachers sending black children to her for disciplinary situations that could have been handled in the classroom.

“Something was amiss,” Zander said. “You cannot look at me as black and think that that child can only be cared for by me because my care is for all the children.”

Decades later, Zander views race relations in America as something that progresses little by little.

“Despite our uneven progress,” she said, “so much about black/white relations is still unsolved. It’s like a layered cake, with some seams still unfound. Each century seems to uncover another layer of racial unrest that is still unexplored. We find another level, then another one.”

When asked if she had advice for today’s African American college graduates, she responded that she had “nothing so profound. Keep moving forward, whatever forward is for you. Forward for each person is following the desire you have for yourself. Keep pushing forward for those desires, and don’t get to the point you say, ‘I can’t do this. It’s impossible. It’s too hard.’ Connect to people who can assist you. There’s always a way.”