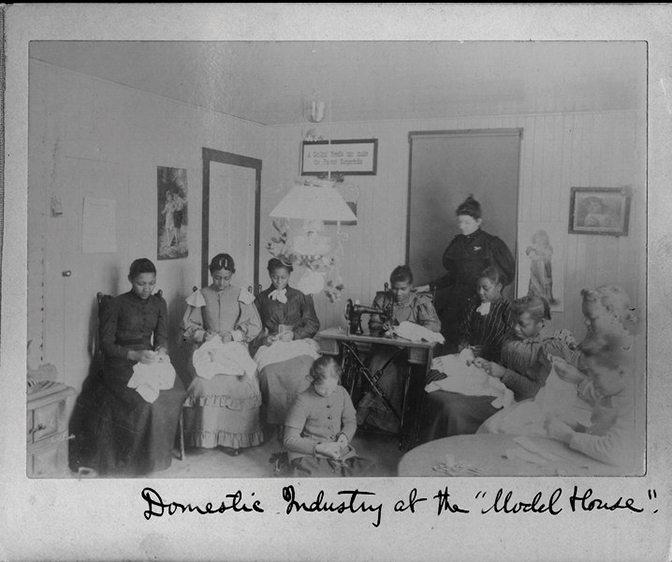

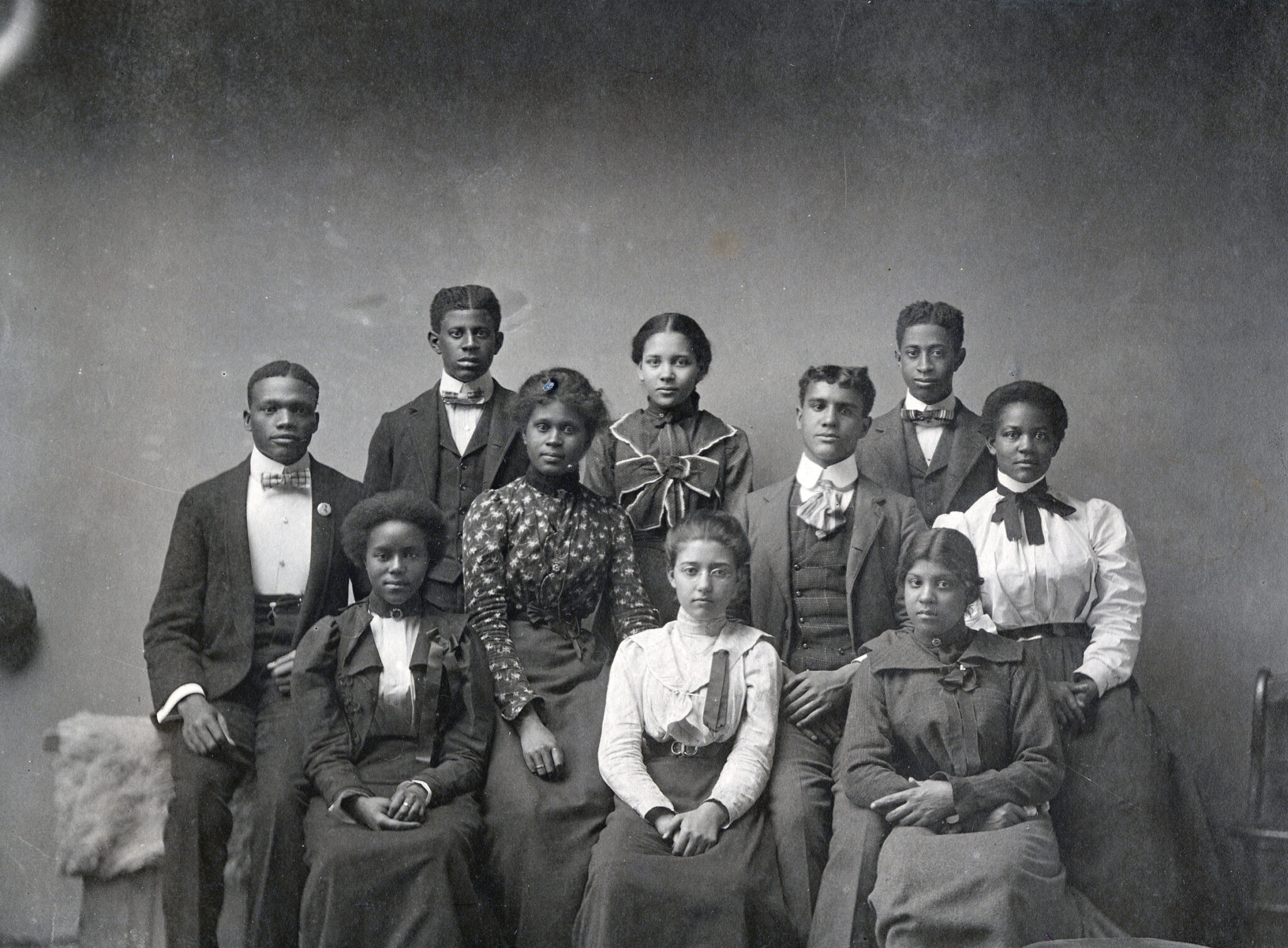

The folklore surrounding the beginnings of the Day Law that forcibly segregated Berea College tells of Carl Day witnessing a farewell embrace of two Berea students at the train station: one student white, one student Black. This innocent moment seized him with a fear that the interracial education students at Berea received was actively harming the white students of Kentucky. Day, who hailed from Breathitt County, defended his proposed legislation, saying it had been introduced “…for the purpose of preventing the contamination of the white children of Kentucky.” Those in favor of the bill expressed their fears that interracial marriage and social equality would be the result if Berea College continued in an interracial manner. The Courier-Journal reported, “It was brought out in the Committee’s investigation today that white and colored girls and boys associate together in classrooms, dining halls, in dormitories and on playgrounds, as well as in social entertainment given by President [William] Frost and others.” Frost and other supporters of Berea tried to quell this fear of interracial marriage and mixing by stressing how “free from scandal” Berea College was, but this fear reemerged in the ruling of Kentucky’s Court of Appeals, which upheld the Day Law, in part, because the State Constitution already segregated public schools and prohibited interracial marriage.

Berea College challenged this ruling by appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court on both First Amendment (freedom of assembly) and 14th Amendment (due process) challenges. The Supreme Court upheld the ruling of the lower court and stayed consistent with the precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson that established “separate but equal” as the law of the land. The majority opinion argued that the State of Kentucky could alter the charter of any private school as it saw fit. This decision allowed for the segregation of all schools in Kentucky, both public and private. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Harlan alluded to the idea that the 14th Amendment represented the idea that the U.S. Constitution was colorblind. This appealing idea, that the Constitution does not make any distinction between the races, forms the basis for later decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka Kansas and recently Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard.

In the time of the Day Law, rumors swirled that efforts to segregate Berea College were politically motivated, originating from outside of the state. Outsiders wanted to control how Berea College educated students and to dictate how we lived out our Great Commitments. Today, as we navigate this new educational landscape where the Supreme Court has argued that race-conscious admissions violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, we must ask ourselves what is the value of interracial education?

Now, 120 years later, we are again facing a challenge. The answer to that fear is holding fast to the common humanity of all people. Our motto, “God has made of one blood all peoples of the Earth,” is more central now than it has been recently. Carl Day’s failure to see the impartial love and kinship in the embrace he witnessed does not have to be our failure, too. By learning to embrace all the humanity of Berea College and to truly learn together as a kinship of all people, we can break down the walls that divide us. It is in this learning to see the kinship of all people through interracial education that helps us truly live our mission as Berea College.

Jessica Klanderud is the director of the Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education and an assistant professor of African and African American Studies at Berea College.

I will love my children go to this college