College archaeologist Dr. Broughton Anderson scrapes the bottom of a test pit to see if a “feature” is present. A feature is a large, non-removable structure like a fire pit or wall.

The forest is full of stories. Until recently, most of those stories came from locals—“old-timers,” Berea College Forester Clint Patterson calls them. Patterson chuckles at how the old-timers’ stories differ from the stories of academics. For instance, on Big Hill stands a rock wall with a disputed origin. A recent scholar declared it a Native American structure. But old-timers say it was built by enslaved Africans at the command of a Confederate sympathizer who sought to protect his homestead from Union troops camped nearby during the Battle of Richmond.

The old-timers know because that Confederate sympathizer was their great-great grandpa.

Other structures in the forest are less debated. The charred ruins of a wayside tavern at Big Hill, known as Grant Cabin, is agreed to have housed the aforementioned Union Army, as well as General Ulysses S. Grant.

“The only thing I like as much as trees is history,” Patterson said. “And there’s history all over this forest, though many wouldn’t know it. Just about any place that’s level is an old home site abandoned more than 100 years ago when the College bought the land.”

What remains of these old homesteads now isn’t much, generally hearths and stone chimneys, provided someone hasn’t four-wheeled onto the property and looted the stones for personal use.

“You can spot them in the winter when the leaves are off,” Patterson said. “You’ll see a pile of stones that used to be a chimney, hand-dug wells. You can see what they planted – yucca plants and daffodils. There are cemeteries, too. It’d be nice to figure out who’s buried in them.”

Patterson relates it is “hearsay” that a 19th century African-American cemetery sits on the south side of Burnt Ridge Road, near a big cedar tree, though it’s unclear which one. Find a big cedar tree and some flat land, he says, and you’re likely to find an old cemetery, though it may be difficult to tell that’s what it was. Instead of tombstones, there are only sunken areas suggesting collapsed resting places. The old-timers say the cemetery is marked by patches of periwinkle.

Dr. Broughton Anderson, assistant professor of archaeology, has identified some places where the cemetery might be. “This area right here,” she said, pointing to a tree-obscured aerial view of the land along Burnt Ridge Road on the computer screen, “is nice and flat, and there are cedar trees and periwinkle.”

She looks forward to winter, when the trees denuded of their leaves become less of an obstacle to finding historical sites scattered throughout the forest. Anderson has become uniquely acquainted with the history of the forest in recent years. Her original and ongoing mission is to survey the forest to better understand the cultural heritage of the area and bring the College into compliance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a 1990 law requiring organizations that receive federal funding to return Native American cultural items to their rightful descendants. Both Shawnee and Cherokee once roamed these woods, and Patterson has been instrumental in safekeeping the cultural and natural heritage of the region.

In 2014, though, the mission branched out into the old homesteads. Anderson secured funding for archaeology internships through the Undergraduate Research and Creative Projects Program (URCPP) to begin surveying the forest for cultural heritage sites. Research in Berea’s Special Collections led them to look into the area off Burnt Ridge Road. What she and her interns found was a deeper and richer history than they had anticipated. Decades before that Confederate sympathizer had his walls built, a formerly enslaved African and his children lived free in these Madison County hills. His name was George White.

“My George White”

Sharyn Mitchell, research services specialist at the Hutchins’ Library Special Collections and Archives, is a bit of a genetic marvel in terms of her family connections to Berea. Among her great-great grandfathers is Cassius Clay, the Kentucky legislator and abolitionist who donated the land upon which Berea was to be built in the 1850s. Another line leads to John D. Harris, an important member of the angry posse that drove Berea College founder and abolitionist John G. Fee out of town due to his views on interracial education. Harris’ enslaved son, Charlie Blythe, later attended Berea College, Mitchell noted.

Anderson’s 2014 archaeology students consulted Mitchell in their hunt for land records pertaining to the area where there were known homesteads that were easily accessible. Berea College bought the land in the early 1900s. A correspondence from Silas Mason, Berea’s first forester, notes the death of “the old slave” and the ability to acquire his land cheaply. The old enslaved African was Richmond Baxter, who came by the land through his wife, Spicey White. Mitchell recognized the names. They, too, were ancestors. Spicey inherited the land from her father, George.

Mitchell calls him “My George White,” a great-great grandfather she discovered through genealogical research. “I had seen his will,” said Mitchell, “so I knew he had left property—hundreds of acres—to his daughters, some at Big Hill, others in Jackson and Rockcastle counties.”

She also had read White’s four-page, dictated autobiography, which details in brief the life of a former frontier enslaved African and his progression toward major landowner. Born in Maryland around 1792, White was brought to the Kentucky frontier by his owner, John White. The experience of frontier enslaved Africans, Anderson said, was different from those on established southern plantations. They often were allowed to travel, to be entrepreneurs, to open bank accounts and carry weapons. John stipulated in his will that upon his death George should be freed as long as the White children unanimously agreed. With a lone holdout among the heirs, other family members purchased George from the auction block in 1828 and set him free in keeping with their father’s wishes.

By 1850, George White owned upwards of 350 acres in northern and southern Madison County and all but one of his six children were free. He secured the purchase of the land by mortgaging the land, household goods and his children. The mortgage stipulated that if he were unable to pay, they could take his livestock first, then the land, and then hire the children out until the entire debt was paid. He paid the debt and freed his children. Some of this land eventually came to be owned by the College via the forest.

The history in this area is most surprising perhaps because of the interracial relationships. By the 1870s, the (George) White family had intermarried with Clay’s descendants in northern Madison County.

Mitchell mentions older relatives recalling how they played in and around White Hall, the estate of Cassius Clay. And at Big Hill, when Spicey inherited the land that originally belonged to Green Clay, the father of Cassius, this was also a community with mixed-race marriages. Though George is buried on his land near White Hall, it is possible the rumored cemetery off Burnt Ridge Road is connected to these families.

“We came to realize there was a substantial community of people of color who owned a good portion of property in the tri-county area,” said Shabria Williamston ’14, who was one of the interns who conducted the back end research. “That’s interesting considering the history of the College, and may be part of the reason the College was founded there in the first place.” The area under investigation is less than five miles from campus.

Research on White and his family continued this summer with another URCPP project in which the team found additional evidence of people living in the area, like nails and screws that match the time period. The deeply wooded site, without trails, can be a difficult hike. Folks living nearby have used the area as a kind of dumping ground. Anderson and crew have to separate modern trash like old appliances and tires from the dig site. Thus begins a long process of unearthing the past—each layer of dirt reveals time gone by. Eventually, something like a button appears, and the particulars of such a mundane artifact can be a confirmation of a time period.

Area families, though not currently linked to the land by deed, are linked by history, with generations growing up in the vicinity. They point out the old well, how they filled it to prevent children from falling in, or where a house once existed. Much of the archaeological work here depends on following up on rumor and legend.

New technology, though, is changing that, and Anderson’s Archaeology 101 students have gotten first-hand experience in both developing and using it.

New tools for an old job

Anderson’s summer research group is never stuck in the classroom. Her students go places—the library, the courthouse and the field. In the case of George White, they located the family’s deeds, read White’s dictated autobiography, consulted the early census records and read about the lives of frontier enslaved Africans from various sources, especially the famous “Free Frank” McWhorter, a former enslaved African from Kentucky who secured his freedom and moved to Illinois to found the utopian community of New Philadelphia. They consulted official court documents to patch stories together in that way, and they also visited the forest to excavate around the homesteads, a meticulous process that develops centimeters at a time in all kinds of weather.

These are the traditional ways archaeology has been conducted over the past century, and they are decidedly low-tech. But modern times bring modern methods. For example, the traditional way of mapping out terrain involved cameras attached to kites. These students are using a geographical information system, a computerized mapping application also used by local governments and emergency managers. And, to add a bit of fun and utility, they fly drones instead of kites.

Samantha Sise ’ 19, one of five archaeology students who made George White their undergraduate research project during the summer 2017 session, says she got “pretty handy” with the drone over the dig site. The traditional methods of archaeology, she said, allowed her to play detective, develop a passion for research and apply skills she picked up through history classes and her labor position in Special Collections and Archives.

“It’s exciting when you get a new lead or something ends up connecting,” Sise said. “You get that ‘a-ha!’ moment, and the story of White’s life becomes more rich and complex—more real.”

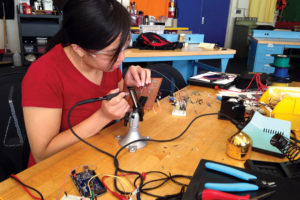

As part of their summer project, Sise and her student colleagues took on a challenge that would benefit future archaeology students. Teaming up with faculty in the computer science department, they built a reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) dome, a small machine spray painted black that allows archaeologists to take better photos in the field without the risk of moving fragile artifacts. With a camera positioned through the top of the dome, an array of 64 LED lights sequentially illuminate objects placed beneath, allowing photos from 64 different angles. The various lighting angles create images with finer detail.

Sise, Alicia Crocker ’19, Bianca Godden ’19, Annie He ’18 and Marisa Snider ’17 built the dome from soup to nuts, a project that pushed history major Sise and English-major Crocker pretty far out of their comfort zones. It wasn’t a walk in the park for Godden and He, either, both computer science majors. The team began with a 200-page instruction manual they downloaded from the Internet.

“I just looked at the pictures,” said Sise. “It was practically a different language.”

Thus began a project that involved writing code for a control box and soldering 128 wires into a perfect pattern.

“Archaeology students were getting their hands dirty with the computer science, electrical engineering,” said Anderson. “They worked on the wiring, the controls, everything.”

“None of the students had a lot of electronics experience,” added Dr. Scott Heggen, assistant professor of computer science, who assisted in the build. [Annie He] was a teaching assistant, but this was much more advanced. Everybody was doing new learning for this.”

It wasn’t a perfect process. At one point, with all 128 wires in place and the code written, the dome didn’t work. After trouble-shooting assistance from Heggen, it was determined the dome was wired correctly except for one problem—they had used the wrong kind of wire. Naturally, this necessitated they rewire the whole thing.

He, eyeing a career in electronics, relished the challenge, and, once completed, the working dome provided “the best feeling of accomplishment,” she said.

Future archaeology students will be able to take the RTI dome into the field. In addition to the pride Anderson and Heggen have in their students, they both express surprise at some similarities between computer science and archaeology.

“In archaeology,” said Heggen, “they define the area they want to dig and build a grid system, dig a few centimeters at a time, sift the dirt. Computer science isn’t that different. You start by defining the problem, break it down into an area, write code for it, and then test it in isolation. The parallels are there in terms of how we solve problems even if they’re completely different fields.”

A new set of archaeology students returned to the forest dig site in November 2017, and each new class will dirty their hands researching and cataloging newly revealed information about George White and his family. Were they connected to Fee and the founding of the college and the town? Were they farmers? What did they farm? What was life like for them in antebellum, frontier Kentucky? These questions and more remain, and Anderson is determined to answer them.