Preserving an Appalachian tradition

Have a conversation with Bill Best ’59, former director of the Sustainable Mountain Agriculture Center, Berea College faculty member and author of two books about heirloom seed saving in Appalachia, and it is likely you’re going to be talking about beans. You’ll learn that there are more bean varieties in Appalachia than anywhere else on earth and that there are 64 bean varieties in Breathitt County, Ky., alone. He’ll tell you there are regional beans, community beans and even family beans, usually named after women.

Bill Best knows a lot about beans. He should. He’s been growing them for 81 years, ever since toddlerhood in North Carolina. When he moved to Kentucky in 1973, he brought his gardening expertise with him and the methods he had learned as a boy. One day, a woman up the road, Lucy Alexander, asked if she could borrow his green house to dry her shuck beans, or “leather britches” as they are known elsewhere, and Best obliged her. When Best observed Lucy’s crop, he commented that her beans always seemed to do better than his.

“Well,” she said, “I’ve noticed you almost always plant in the wrong sign.”

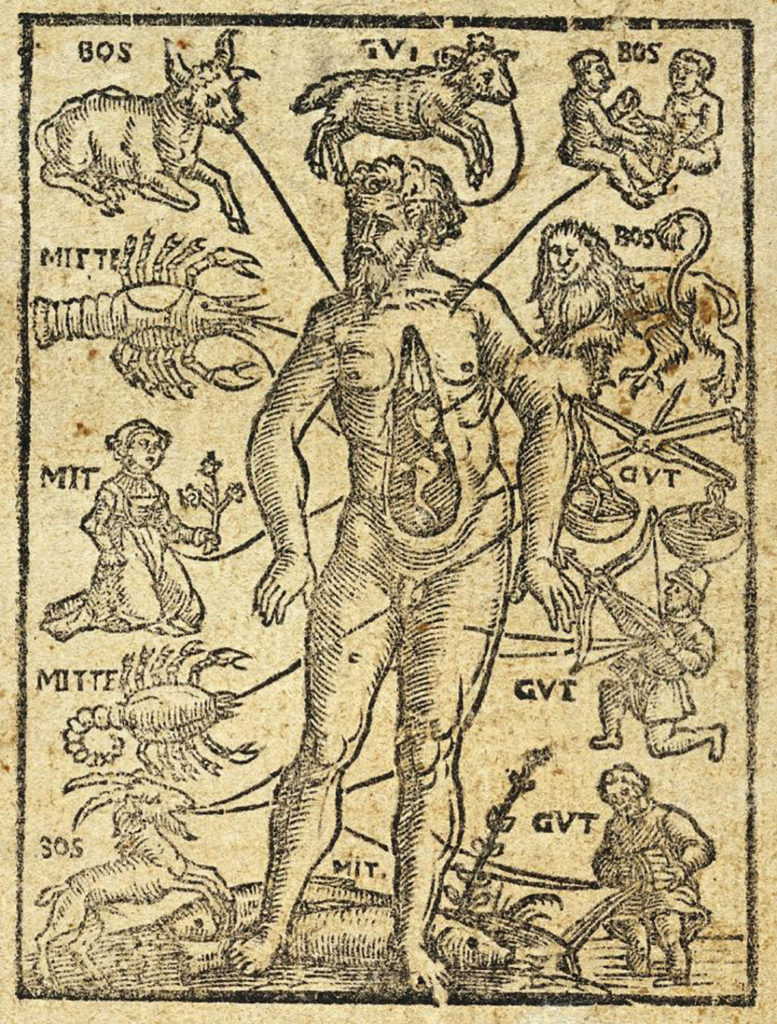

What Lucy was referring to is the old Appalachian tradition of planting crops according to astrological signs appearing within the moon cycle. For beans, you want to plant when the moon is in Gemini. Only that’s not what the Appalachian “old timers” will say. They’ll say you plant beans “in the arms.” This refers to the “Man of the Signs,” an ancient sketch that assigns body parts to represent the astrological signs favorable or unfavorable to planting, or a number of other activities.

Lucy marked a calendar for Bill, noting the best times to plant, and the next year, lo and behold, his beans did better.

“It’s been my observation that beans come out better when planting by the signs,” Best said. “I think there has to be something to it because if the moon can affect the tides, then it can probably affect the growth of plants. A lot of people in the mountains did everything by the signs, cutting brush, even castrating animals.”

Bill’s story is just one of dozens of oral histories being collected for a project called “Beans in the Arms: Planting by the Signs in Kentucky.” Dr. Sarah Hall, plant ecologist and associate professor in the Agriculture and Natural Resources department, began collecting these histories through recorded interviews with people throughout central and eastern Kentucky last fall. The work is made possible by a grant from the Kentucky Oral History Commission.

“I am a trained scientist, so this work is certainly out of my realm of expertise,” Hall said, acknowledging that her background made it difficult for her to accept the practice. “But the part of me that loves this region is fascinated by it, and when something has been done and followed for so long by so many, I think there could be something to it.”

Hall first encountered the practice in 2010, when working at a research farm at Kentucky State University. A man named John Clay handed her a bag of mush melon seeds and advised her that if she planted them under a certain sign, they would grow an inch deeper into the soil. The Madison County native tucked the seeds and the advice away and did not think much about it again until teaching a course called “Appalachian Plants and People,” focusing on plant traditions related to medicine, food and craft—many of which are being lost over time.

Planting by the signs appears to be one of those traditions that is not being carried on by the younger generations, reason enough for Hall to spend her sabbatical researching and archiving information about it.

“The older folks have told us that their grandchildren don’t follow the signs anymore,” said photographer Meg Wilson, whom Hall brought on to the project to photograph the people interviewed. “This older generation of grandparents and great grandparents have practiced planting by the signs for 60, 70, 80 years. And they say that the younger generation is too busy to follow it.”

“We’ve talked to quite a few people who said, ‘I wish you could talk to my uncle about it, but he passed away two years ago,’ Hall said. “There’s a feeling of urgency to capture it because people are getting older.”

Best concurs that the tradition doesn’t seem to be catching on with the younger folks. “I think we skipped a couple generations where the lore wasn’t past on,” he said. “A lot of the younger people are moving back into gardening now for nutritional purposes and to get exercise, but not a lot them are returning to the signs.”

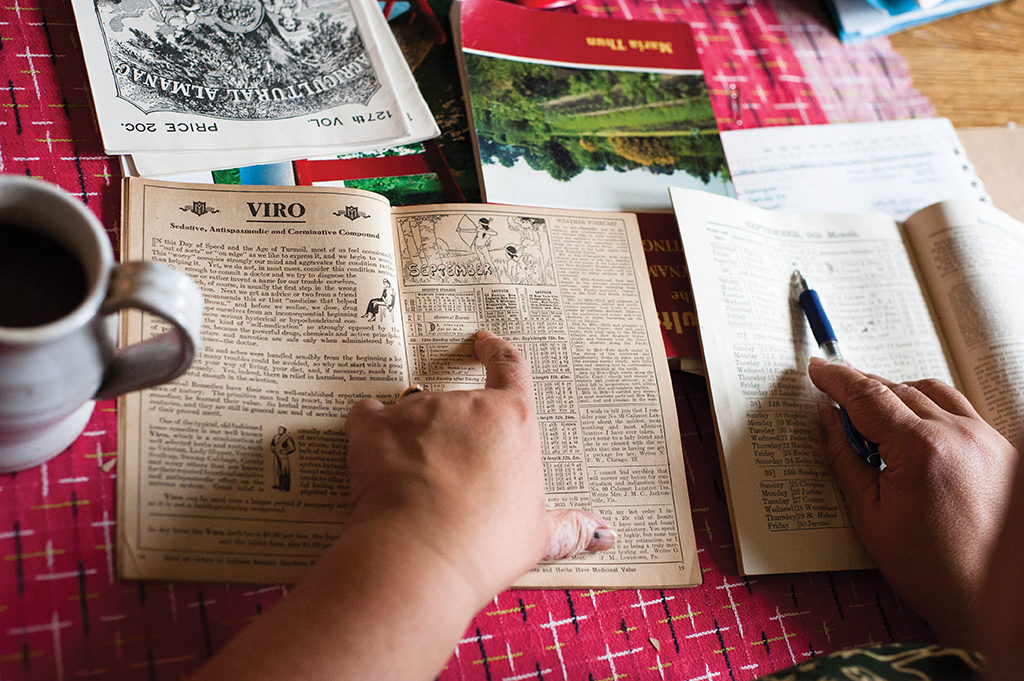

There is a dearth of research into the practice, and almost no testing scientifically—even though the tradition is quite old; it is even mentioned in ancient Mayan texts. Hall relates that one German researcher conducted testing with positive results and developed a new kind of “biodynamic” calendar with different symbology. But other than what’s contained in the Farmer’s Almanac, the Foxfire book series, which details southern Appalachian traditions, and a few distributed calendars, there is very little information about planting by the signs outside of oral and family traditions, most often passed down by women.

If desired, a person could live their entire life by the signs in this tradition. There are good fishing days, days for curing hogs, good and bad travel days. There’s even guidance for having surgery or getting dental work. It’s best to schedule medical procedures when the sign is away from that particular body part. For dental work, pick a sign below the knees. And whatever you do, never plant or make sauerkraut “in the bowels” or it will turn bad.

One person featured in the collection, planned for publication by University Press of Kentucky, is Berea alumna Jane Post ’81, a homesteader who grows vegetables and mushrooms on 200 acres outside of Berea and hosts retreats there. For just about everything, Post follows “Llewellyn’s Moon Sign Book,” in publication since 1905.

“I highly recommend it,” Post said. “You can basically run your whole life by it. It even tells you when to wean your children. When we advertise by email, I pick a sign that’s good for communication.”

When she schedules retreats, Post ensures safe travel of guests by choosing days outside of a Mars aspect, when accidents are more likely to happen. The moon sign book can be followed in difficult weather as well, Post says.

“During a drought, it really matters,” she said. When I plant by the fruitful signs, a water sign like Cancer, I will get rain. It’s not very scientific, but it’s as close to science as I come.”

Though a scientist, Hall says testing the practice to see if it holds up isn’t really the point of the project. The point is the stories, the history and the preservation of tradition, though in the future she may test out a few rows.

Wilson agrees that preserving the history is what matters most. “It’s important that the people we talk to are able to tell their own stories and share their memories of their connection with the land and preserve that for future reference,” she said. “We often feel history is so far removed from us, but it’s not that far removed. It exists within living memory.”

Hall and Wilson will wrap up the interviews for the project this year, with audio of the full interviews made available on the Hutchins Library’s Special Collections & Archives website, and a book to follow.