By Jason Lee Miller

In 2003, Dr. Emily Auerbach, professor of 19th century literature at the University of Wisconsin (UW)-Madison, fulfilled an ambition she had nursed for many years. She began an educational outreach program, called the Odyssey Project, in one of the poorest neighborhoods in Madison. However, unlike many programs designed to give adults a second chance, the team taught UW Odyssey Project does not focus on job skills or training.

Instead, it offers access to the liberal arts. The two-semester program introduces participants to the writings of a diverse group, including Shakespeare, Martin Luther King, Jr., Emily Dickinson, William Blake and Plato. Afterwards, students are offered various kinds of assistance to transition into college.

Like Berea, Odyssey is tuition-free. The program addresses other barriers to entry as well, such as the cost of books and child care – even incarceration. When one student landed back in jail, Emily sent his homework there. Eventually, he graduated.

About two-thirds of Odyssey students continue on toward associate’s and bachelor’s degrees, and some their graduate degrees. Taking advantage of an opportunity not often extended to their community, they use it as a way out and a way up. While the success of the Odyssey program is now clear, people were slow to embrace the idea in the beginning.

“Why would poor people want to read Plato?” a local reporter once asked Dr. Auerbach. To understand their motivation, one needs to hear the stories of Emily’s parents.

The Power of Words in Appalachia

Just outside of Knoxville, Tennessee, in the little town of Powell Station, young Wanda Irwin, ’50, watched her mother, Gustava, open hate mail from the locals – mail her father, William, a part-time mail carrier, had delivered. Mrs. Irwin was a teacher who voiced unpopular opinions against the racism of the 1930s.

They could hardly afford the controversy. The Irwin family had very little money and their home had no running water.

“My mother remembered being hungry, having hand-me-down clothes,” Emily said. Not that Gustava would have people feeling sorry for them. “The local church would come with clothes. My grandmother would tell them they didn’t need anything because she could smell the pity from a mile away. There’s a kind of charity that demeans people.”

But at least there were books. Barefoot, Wanda walked miles to the nearest bookmobile. “I stayed in on beautiful sunny days and memorized poetry,” said Wanda, in a documentary about her daughter’s project. “That’s the kind of person I was. I was weird.”

Emily suggests that Wanda’s love of literature was a form of escape. “Reading helps people transcend the limitations of their lives,” Emily explained.

Wanda graduated early from high school. But without money to “escape” to college, the mountains surrounding her hamlet closed in around her. Then, a cousin told her about Berea College, a school founded to serve people in her situation.

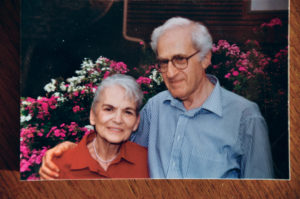

“Wanda would never have been able to go to any other college,” said Dr. Robert Auerbach, ’49, Wanda’s future husband, who has his own story of escape.

Legal Distinctions in Berlin

In 1930s Berlin, Robert Auerbach’s parents, Ella and Richard, were accomplished lawyers. Ella was the first woman to be admitted to Berlin’s Supreme Court, and Richard, also a practicing lawyer, was a World War I recipient of the Iron Cross, a military medal of honor.

With the rise of the Nazi Party, however, there came to be an even more significant distinction – the Auerbachs were Jews.

“Being Jewish had its consequences,” said Robert, in his trademark wry understatement. Over time, many of these consequences would grow in severity.

As Germany moved toward war, Jewish families were permitted only one wage earner, and Jewish lawyers could only serve Jewish clients. Eventually, Jewish lawyers were denied licenses altogether and forced to flee Germany.

But because Hitler honored the Iron Cross, Richard was able to continue practicing law after his colleagues had left. The ultimate consequence, however, was the impending threat of the concentration camp. “My father hid, disappeared,” said Robert. “I didn’t know where, but I think my mother knew.”

Ella knew other things, too, like how to exploit the German government’s exacting devotion to bureaucracy. Using legal loopholes, she was able to procure an exit permit for the family to Siam (now known as Thailand).

“They wanted to put us in a concentration camp, but instead gave us permission to leave,” chuckled Robert, noting also that instead of traveling to Siam, the Auerbachs disembarked in London, having obtained a transit visa for refugees.

They settled briefly and peacefully in England, but as the threat of German invasion intensified, the Auerbachs were separated. Robert was evacuated with his schoolmates to a castle in Wales, his sister to another in northern England. Mrs. Auerbach moved away from the coast to London, and Mr. Auerbach was interned at a camp on the Isle of Man.

“Nobody knew where the others were,” said Robert. “We wrote letters trying to find each other.”

In September 1940, the family received U.S. visas, and made their separate ways to Glasgow, where the HMS Cameronia waited to take them to New York. Robert and his sister reunited at a London train station on the first day of the Blitz.

“The station had a glass roof,” recalled Robert, “and up in the sky were the German bombers.” Because of the German bombing raid they were late, but the ship was still in dock. Their parents met them on board.

“It was not the best time to cross the Atlantic,” said Robert, still understating, and the ship swung toward Iceland to avoid German U-boats. By the time the Statue of Liberty appeared on the horizon, word had gotten around the Cameronia that young Robert was a piano player. “Somebody asked if I could play ‘Harbor Lights,’ and since I didn’t know it they had to sing it to me,” he said.

“He still chokes up about that story,” added Emily.

As the family rebuilt their lives in New York, the Auerbachs learned that Berea College in Kentucky had set aside some open slots for war refugees, something a group of New York Quakers had arranged.

“The only requirement,” said Robert, “was we should not object to church on Sunday, but if we wanted to go to Synagogue, we could.”

Music and Education, But Above All Love

“I was very young – I went to Berea before I was 17. I did not have any idea what my future would be like.” Though he played piano and oboe, Robert chose a major in biology over music.

That’s not to say he was no longer musical. “My job the first year was changing bed pans in the hospital, but then I was ringing the chimes at Phelps Stokes Chapel. People didn’t envy me. I had to be there every morning at 6:00 a.m., and then again at noon and 5:00 p.m. It was physical work ringing those bells. I was not envied, but I liked it. I worked out some unorthodox arrangements.”

Robert’s “unorthodox” arrangements were often weather reports in code – “Oh What a Beautiful Morning,” “Rain” and “Let It Snow.”

Though one might assume the point of his attendance at Berea was the quality liberal arts education he was receiving, Robert sees it differently. “The main point,” he says, more than 65 years later, “was to meet my wife.”

After their exodus from Germany, the Auerbachs were improving their situation in New York, but Wanda’s situation was about to get worse.

“She didn’t have money for soap,” said Emily, explaining that Wanda would hunt through shower stalls for soap remnants to combine into a cake she could use. No money for soap, and no money when things got even harder.

“Her father died while she was at Berea,” explained Emily, “but she didn’t have money to go to his funeral. A kind dean gave her the money.”

“I wish there was a video of my German grandfather trying to talk with Tennessee Appalachians.”

“That was Dean [Julia] Allen,” added Robert, in a separate conversation. “Wanda dropped out for a semester and then was on the half-day plan [so she could work].”

The first-generation college student from Powell Station had very little money, but she had an active mind – eventually she would graduate as the valedictorian of the class of 1950 – and she had Robert, even if the young man’s musical abilities kept him in demand elsewhere.

“It was hard on Wanda because every time there was a dance, I had to play instead of dance.”

The young couple married in Berea’s Danforth Chapel, with W. Gordon Ross, the chair of the philosophy department, presiding over the ceremony in English, German and Hebrew. The wedding cost $500, all borrowed.

“Everybody came,” said Emily, referring to family, students and faculty. “I wish there was a video of my German grandfather trying to talk with Tennessee Appalachians.”

Emily and the Legacy of Berea

Emily doubts anyone anticipated that her parents’ “spiritual union” would last 62 years – until Wanda passed away in 2012. “I think their story illustrates Berea’s mission – that people can find a common humanity – very well. I’m aware of that every day of my life because of my parents. A lot of what I do is because of Berea. “

A lot of what Emily does is make the tough sell that a more classical education can help lift people out of the cycle of poverty, or that it will help them at all.

“There is a mindset about the poor,” she said. “They’ve been told they’re dumb. They’ve been written off, but I’ve had better discussions about Plato with them than with students elsewhere. Some relate the ‘Allegory of the Cave’ to when they had been incarcerated. Their responses take you to a deep level.”

Her thoughts carry echoes of her mother. “My mother told me all people have a craving to encounter art, and poor people are closer to issues of injustice and suffering, so they respond more viscerally to some of the material.”

The Odyssey Project is bearing fruit. Emily notes that she has students who have moved from homelessness to graduate school.

In the aforementioned documentary, a man addresses a cheering crowd. “I’ve been redeemed,” he says. “I went from [being] a drug addict, alcoholic, drug-dealing and gang-banging thug to a hard-working man of God who visits and preaches to those who are behind bars.” He punctuates his statement with a resounding “hallelujah.”

“It’s fantastic,” said Robert. “Emily’s goal is to convince the University of Wisconsin to ‘have a Berea.’” He continued, “She thinks people should be able to go to school, and she thinks you shouldn’t give up on people who have had a hard time. Education can generate a lifelong change for people.”

For more information about the Odyssey Project and the Auerbach family, please see the video, Forward Motion–The Odyssey Project, that originally aired on the Big 10 Network. It can be accessed here.

[…] and beyond over his long lifetime, but dearest to his heart are donations and planned gifts to Berea College, where he received a tuition-free college education and met his wife, and the UW Odyssey Project, […]