Though I grew up in eastern Kentucky, my route to Berea College was circuitous.

I had an idyllic childhood at Boones Creek Baptist Camp in Clark County, hiking and riding horses in the foothills and living in immediate proximity to nature. I created “books” for my parents with protagonists like foxes, bobcats, raccoons and opossums. The only sadness I recall was seeing these wild creatures killed by vehicles on our narrow, winding country roads.

Graduating from George Rogers Clark High School in 1981, I was aware of Berea College and its positive impact on the region. But I started my higher education at Kansas State University, taking classes part-time and working at a bookstore while my husband attended graduate school. One day on my way to work, I watched in horror as my tires crushed an unsuspecting box turtle. Its unnecessary death at my own hands had a profound effect—and would play a role in my future.

By the time I transferred my credits to Berea in 1987, my marriage was at an impasse. Having only just arrived in this long-standing, tightly knit community, I found myself in the midst of a divorce. Lacking confidence in the face of emotional and social upheaval, I struggled to show up as the dedicated student I wanted to be.

Two professors came to my rescue. One English professor, Gene Startzman, had a benevolent but mischievous grin that introduced a measure of joy into my despair. He helped me take my writing to the next level, showing me how to discover innovative connections and then express them for the best creative effect. My industrious, service-oriented Spanish professor, Fred de Rosset ’72, saw my potential and secured me a teaching assistant position helping others strengthen their writing. Neither gave up on me when personal turmoil prevented me from meeting my obligations. Both taught me by example how to catalyze empathy.

Just as I began to see light at the end of the tunnel before my May 1992 graduation ceremony, my father died unexpectedly. Focused on helping my mother and earning a living, I departed Berea and, for a long time, never looked back.

Writing for the advertising department at the Lexington Herald-Leader, I traveled curvy roads from my farmhouse to downtown each day, intently focused on not hitting wildlife. I hadn’t been on the job long when a pair of furtive brown eyes peered over my cubicle. “I hear you’re a Berea grad,” the stranger said. “So am I. Let’s talk.”

It was Jim Durham ’69, community editor for the newspaper and my third Berean mentor. He arranged for me to cross-train in the newsroom, and, for years, I wrote under his direction as a freelancer. He taught me to consider my audience, see an issue from the reader’s perspective and quote key voices that would draw folks in and keep them reading. Like Startzman and de Rosset, Durham led from a place of empathy, a Berea-born value.

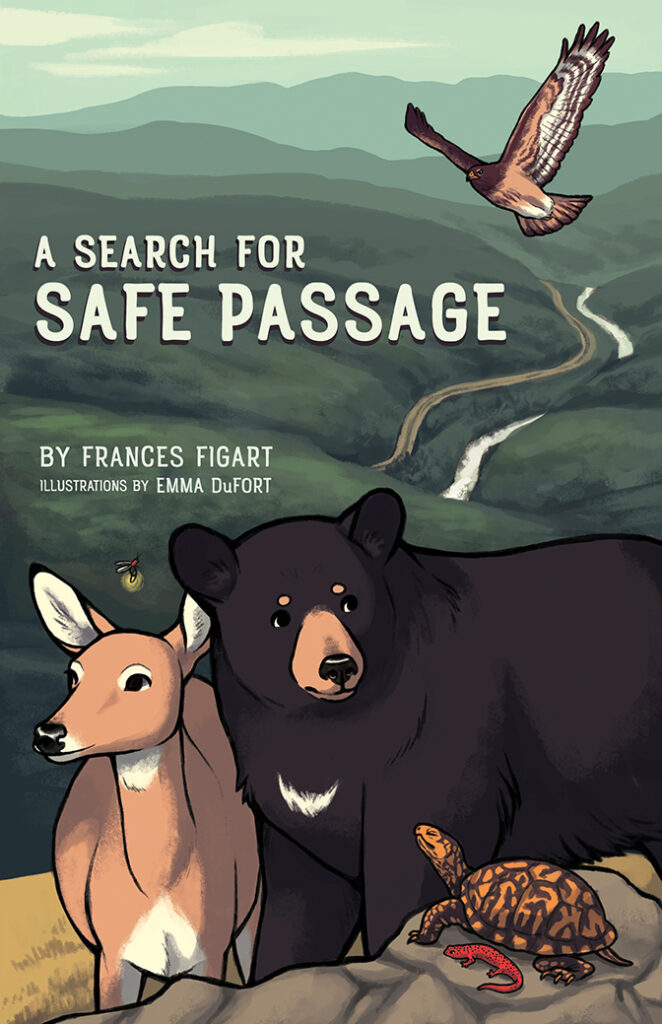

Published by Great Smoky Mountains Association in 2021, “A Search for Safe Passage,” is geared toward ages 7-13, yet it is also a fable appropriate to be enjoyed by wildlife loving adults of any age. It features 19 species of wildlife found in Southern Appalachia. In the final chapter, the animals are all reunited on the “landbridge” after having been separated while one group was traveling on the south side of the gorge and the other remained in the north. You can purchase the book online here.

I became a travel magazine editor and an ecotourism journalist. Wherever I went, from the tropical rainforest of Central America to the Bay of Fundy in Atlantic Canada, I saw roadkill. I learned that road ecology—how plants and animals are affected when roads are nearby—is a global issue that many countries have already begun to address.

Finally, in 2017, the problem reached a tipping point—both for me and for southern Appalachia. I began to see black bears and even elk killed on Interstate 26 near my new home north of Asheville, N.C. Networking led me to a group of organizations beginning to research wildlife mortality along Interstate 40 near the boundary of Great Smoky Mountains National Park—the park at which I was working.

Folding my passion into my job, I helped the group brand as Safe Passage: The I-40 Pigeon River Gorge Wildlife Crossing Project. My employer, Great Smoky Mountains Association, joined other organizations creating a fund to raise private dollars for wildlife crossing structures. I wrote and directed dozens of articles about on-the-ground research, which involved tracking elk movement via GPS-fitted collars and deploying wildlife cameras to reveal where animals were getting killed in vehicle collisions.

As COVID-19 lockdown set in, a friend suggested I write a children’s book about the issue. I protested that I had too many projects already and was not trained to write for kids. But then I imagined my Berea mentors as a Greek chorus asking: Why not create a story you would have loved to read with your parents as an 11-year-old in the mountains of eastern Kentucky?

I looked at the wildlife-camera footage and wondered what it would be like to be a bear, a deer, an elk, a bobcat, a salamander, a frog, a turtle—each trying to navigate a terrifying highway. I recalled what it felt like to be faced with immense challenges and to be given a second chance. I invoked what I had learned about connecting ideas in innovative ways to engage an audience emotionally. I wrote eight fictional chapters from the perspective of 19 anthropomorphized southern Appalachian animals and followed that with an educational section about the real species and how to help them cross, showing structures that have reduced mortality across the planet. I even wrote a song, “Safe Passage: Animals Need a Hand,” which appears as sheet music in the book and as a music video on YouTube.

Today, 30 years after graduating from Berea, I direct a team of writers, editors, graphic designers, photographers, illustrators and videographers who interpret the natural resources of the most-visited national park in the U.S. “A Search for Safe Passage” was named 2022 Publication of the Year by the Public Lands Alliance. State and federal funds are floating in to accompany grassroots dollars and road ecology research is expanding to I-26 near the home I share with my husband of seven years.

In April, I drove past construction that will eventually result in a wildlife underpass on I-40. I was on the way to visit my three Berea mentors. I gave them signed copies of my book and thanked them for their encouragement and the opportunities for growth they provided during uncertain times.

I don’t know how many years it will take us to realize the dream of a large wildlife overpass in southern Appalachia. But I have no doubt the empathy fostered at Berea will continue to affect my life—and the lives of wild animals—down the road.