On Oct. 14, 1960, at 2 a.m., a young crowd eagerly anticipated the words of John F. Kennedy as he took the steps outside the University of Michigan’s student union.

“How many of you are willing to spend 10 years in Africa or Latin America or Asia working for the U.S. and working for freedom?” he asked the crowd. Their youthful enthusiasm cemented Kennedy’s decision to create the Peace Corps in 1961, one of his first acts as president. But this isn’t about Kennedy. It’s about a particular “footnote” in the history of the Peace Corps.

Half a century later, another crowd gathered in Ann Arbor, Michigan, for a parade. Among the procession, a man dressed as Uncle Sam displayed his infectious patriotism as he passed. Likely, they hadn’t the slightest idea the man in the tall, star-spangled hat had envisioned what would become the Peace Corps on the grounds of Berea College in 1951.

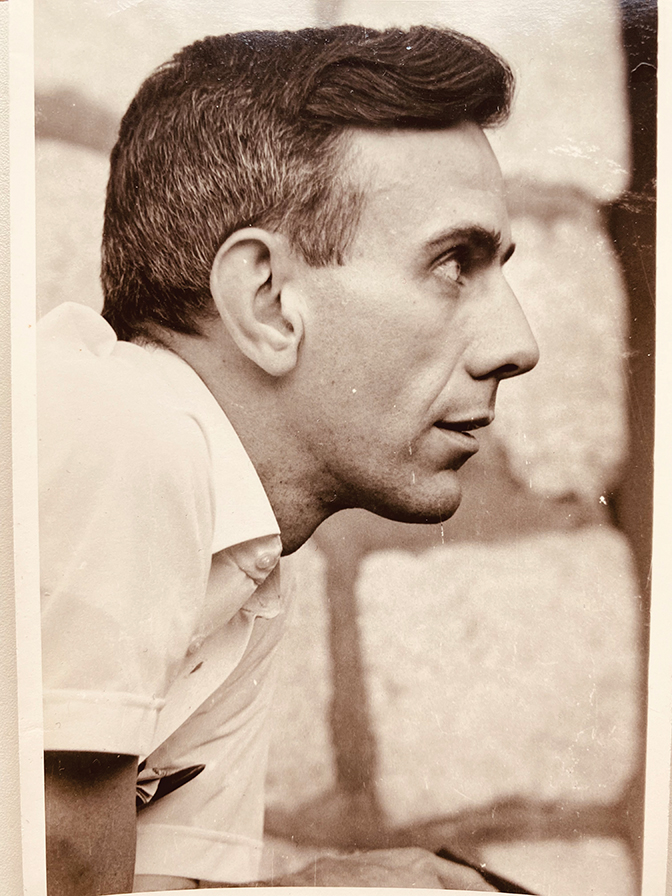

According to one account of his life, Doug Kelley ’51 only ever admitted to telling one lie. He was 15 in 1944, but to become a page at the Democratic National Convention, one had to be 16. His dad was a Republican and a federal highway engineer. But Doug was a Roosevelt man. He returned from paging at the Democratic National Convention with an armful of campaign materials—the beginning of a collection that would grow so large a special building was required house it.

Soon afterward, teenage Kelley read “Reveille for Radicals” by veteran Chicago organizer Saul Alinsky and wrote a review for his high school newspaper.

“What’s this review you wrote about a book for radicals?” his principal asked him, according to Peter Kelley, Doug’s son. “I’m not sure that’s the kind of thing we want in our high school newspaper.”

His principal’s suspicion did not curb Kelley’s enthusiasm. The next year, in 1947, as a first-year student at Michigan State University, he met Bill Welsh ’49 in Madison, Wisc., who became the first president of the National Student Association before taking jobs with the Democratic National Convention and for U.S. Senator Hubert Humphrey.

“He heard about Berea and thought this is the kind of place I want to go to,” related Peter. “My people are going to be at Berea.”

So, he traveled to Kentucky and, though he was not the typical Berea student, his “relentless enthusiasm” allowed him to “talk his way in.” He majored in history and political science; he shoveled manure at the dairy farm; he wrote for the Pinnacle, Berea’s student newspaper.

In 1951, about to graduate, Kelley had been serving as the national chair of Students for Democratic Action and was in touch with George Shepherd at the London School of Economics, along with Julius Kiano (the first Kenyan to obtain a Ph.D. ) and Nelson Jonnes (inventor of polywater lubricant) at Antioch College. These four hatched the idea for the International Development Placement Association (IDPA), along with Berea classmate Galen Martin ’51, the future executive director of the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights and author of the state’s 1966 civil rights legislation. The IDPA would place people in modestly paid jobs with indigenous organizations and governments in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

At Berea, Kelley also met Mary Louise Corsi ’51, the Appalachian daughter of an Italian immigrant clarinet player and barber. Kelley first laid eyes on Corsi as she played the bass fiddle in the orchestra. He proposed marriage. She told him no.

So, on June 12, 1951, the recent Berea grad sent a three-page letter to 65 student leaders in many states to pitch the idea of the IDPA. By the fall, he had secured endorsements from Tennessee Valley Authority chairman David Lilienthal and American Civil Liberties Union founder Roger Baldwin.

And on Dec. 6, 1951, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas wrote in support of the IDPA, saying, “These emissaries will do more to build understanding between these two worlds than all the wealth and all the military might America can muster.”

Kelley left his fledgling organization in the hands of friends. Peter Weiss became executive director and moved the IDPA to the Carnegie Endowment International Center, two blocks from the United Nations. Other friends involved in the startup were future U.S. Senator Harris Wofford and workplace safety pioneer Frank Wallick.

In 1953, Kelley married Cynthia Gebauer, whom he met when she volunteered to take notes at an IDPA organizing meeting, and the newlyweds hopped a freighter across the ocean for a “hitchhiking honeymoon” in Europe and Asia. Their goal was India, where they spent several months living in spartan conditions in Sevagram, Mahatma Ghandi’s service village.

“My mom would say that wasn’t her idea of a honeymoon,” Peter related, noting also that she carried a metal suitcase with the Thomas Paine quotation, “The world is my country and to do good is my religion,” painted on the side.

Back in the States, the IDPA struggled. In its first three years, 18 volunteers had been placed in teaching and social service positions around the world, and another 502 had applied, but operating on such a small scale proved costly, and the organization nearly folded in 1954.

But Kelley still had his knack for impressing influential people. As Kelley worked for Michigan’s Lt. Gov. and future U.S. Senator Phil Hart, Wallick became an assistant to U.S. Congressman Henry Reuss of Wisconsin.

Wallick put the idea in front of Reuss, who introduced a bill in the House of Representatives and recruited

Humphrey, who introduced “the Peace Corps bill” in the Senate. Meanwhile, Kelley joined Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom at the Lincoln Memorial, got himself arrested for participating in a civil rights sit-in and made friends with Langston Hughes while volunteering with the NAACP.

When Humphrey lost to Kennedy in the Democratic primary, he sent Kennedy his top five ideas, which included the Peace Corps. Kennedy established it officially by executive order in March 1961. On Feb. 18 of that year, Kelley received a telegram from the president’s brother-in-law, Sargent Shriver, saying, “If you want to work on Peace Corps come to Washington Monday. We may be able to use you right away.”

That telegram now resides in the Smithsonian.

Kelley began his new job as director of community relations at the organization he inspired. But living and working in Washington, D.C., wasn’t what Kelley had in mind.

“After a very satisfying year in that job, I sent Sargent Shriver a memo explaining that I’d rather be overseas, out in the boondocks, doing the kinds of work we were urging so many others to volunteer for,” Kelley wrote.

Kelley, his wife, and two young sons then moved into a mud-brick house in Cameroon.

“No electricity or plumbing,” Doug Kelley wrote, “but GREAT landscaping and great neighbors.”

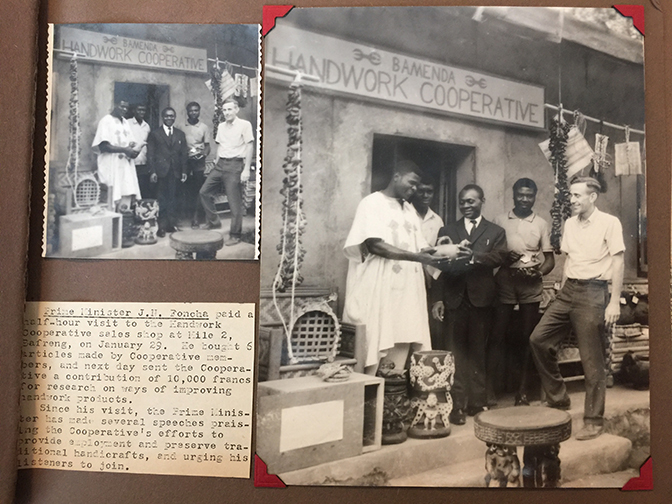

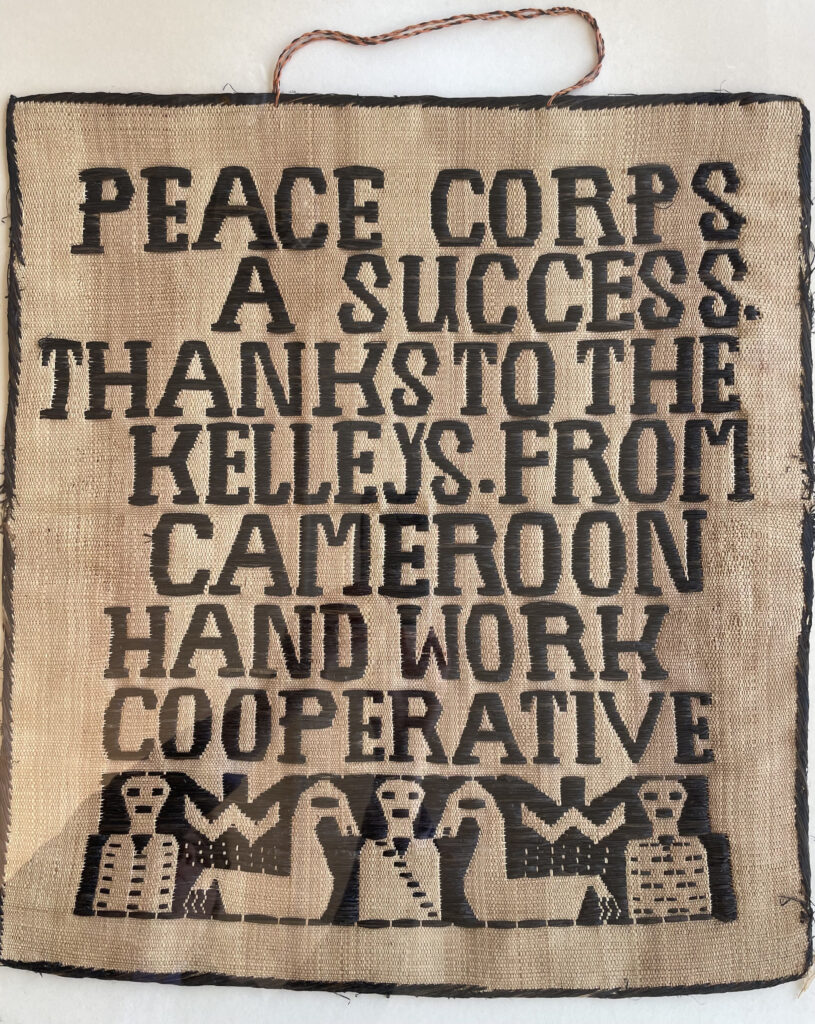

While the Kelleys were in Cameroon in the early 1960s, Doug led the establishment of a 1,300-member crafts marketing cooperative of artisans who soon doubled their monthly income.

“My dad came out of Berea with a love for handicrafts,” Peter Kelley said. “So, in Cameroon he said let’s have a craft cooperative. We’ll collect the wood carvings, the bead work, the traditional masks, stools, embroidery, brass figures and musical instruments and create a market for it. The Bamenda Handicraft Cooperative Society still exists. I’m in touch with the woman who runs it on Facebook.”

One day, in New York, Kelley happened upon a pair of African basketry-covered musical shakers at the Lincoln Center’s Philharmonic Hall. The tag had his handwriting on it. Kelley sent a postcard to the man who made them, which was read to him by a young boy: “Your shakers are being sold in THIS BUILDING in New York City.”

Doug Kelley went on to do a great many things in his life. In 1966, he was assaulted in Mississippi by “bottle-wielding racists” as he recruited for a multiracial training program. He earned his Ph.D. and settled in as a college professor and extension director at the University of Michigan. And, when he found himself single again, Kelley reached out to Mary Corsi through the Berea College alumni office. When Corsi received his letter, she said, “Oh, it’s Douglas Kelley. He’s going to ask me to marry him.”

Twenty-seven years after Doug Kelley asked Mary Corsi to marry him the first time, she said yes. They were wed in Berea’s Danforth Chapel and were married until Corsi’s death in 2015 at age 85. During their 37 years together, Corsi grew tired of the presidential memorabilia cluttering up the house, so she built him a two-story museum in the backyard. He named it, simply, The Democratic Archive, and it contained campaign materials from Thomas Jefferson to Barack Obama. It also became a Democratic hangout where one might run into Barney Frank or John Dingell.

“Don’t miss the Harry Truman bathroom!” Kelley wrote to would-be visitors.

After Corsi passed, Kelley spent the last six years of his life in Glacier Hills Senior Living Community in Ann Arbor, where he met his third wife, Ellen Brady Finn, a retired English and Latin teacher, who lived across the hall. The wing where they resided came to be known as Kelley East and Kelley West.

Doug Kelley died in January 2022. He was 92 years old. Peter Kelley says his dad claimed to only be a “footnote” in the history of the Peace Corps. His collection of presidential campaign memorabilia has been divided up among presidential libraries across the country.