In the summer of 1968, following graduation from Berea College, I had a full scholarship to attend graduate school at Johns Hopkins University. A Ford Foundation staff member showed up on campus to recruit an Appalachian to be part of the Foundation’s new leadership development program. Former Berea professor Bill Best ’59 suggested to him I would be a good candidate. I dropped the idea of graduate school and became a Ford Foundation Fellow with a stipend for expenses to cover a year of learning about economic development.

In January 1969, I landed at the newly founded Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) in Washington, D.C. To my astonishment, I was a bit of a celebrity because I was one of three or four people out of about 125 at the agency who was from the region, and quite a few of the staff knew the reputation of Berea College. I persuaded the agency to start a youth leadership development program and got busy increasing the number of Appalachians at the agency. I hired Betty Jean Hall ’68, Garry Abrams ’69 and Barbara Durr Fleming ’68 full time and Jan Hill Reid ’69 as an intern.

We were a small infiltrating army of Bereans at an agency that had described Appalachia as “an island of poverty in a sea of affluence.” We had some success in starting new programs around the region, but investing in people was not that popular in an agency geared to invest in “things” such as roads, vocational schools and a variety of other public works programs.

ARC has had some successes in Central Appalachia, the 60-county region that ARC identifies as the main coal-mining counties in four states. There now are better roads in the region. The agency provided funding for the redevelopment of Pikeville, Ky., and Grundy, Va., turning Pikeville into a celebrated growth center at one time and solving major flooding issues in both places.

I remember a statistic from my time at ARC: Central Appalachia residents had median income that was about 64 percent of the average income in the U.S. Today, Central Appalachia has median income of 62.2 percent of the nation, primarily because of the dramatic decline in coal production and partly because none of the war-on-poverty programs launched in the 1960s had a very dramatic long-lasting impact. President Lyndon Johnson declared the War on Poverty at Tom Fletcher’s home in Martin County, Ky. Fletcher, who was enrolled in a new job training program, learned to change spark plugs, he said, but never found a job. Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman passed out the first food stamps in the U.S. in Mingo County, W. Va., keeping President John F. Kennedy’s pledge to “do something” when he campaigned there for president. Mingo County has now lost a higher percentage of its population since 1970 than any other county in the U.S. Martin County remains one of the poorest in the country, as well.

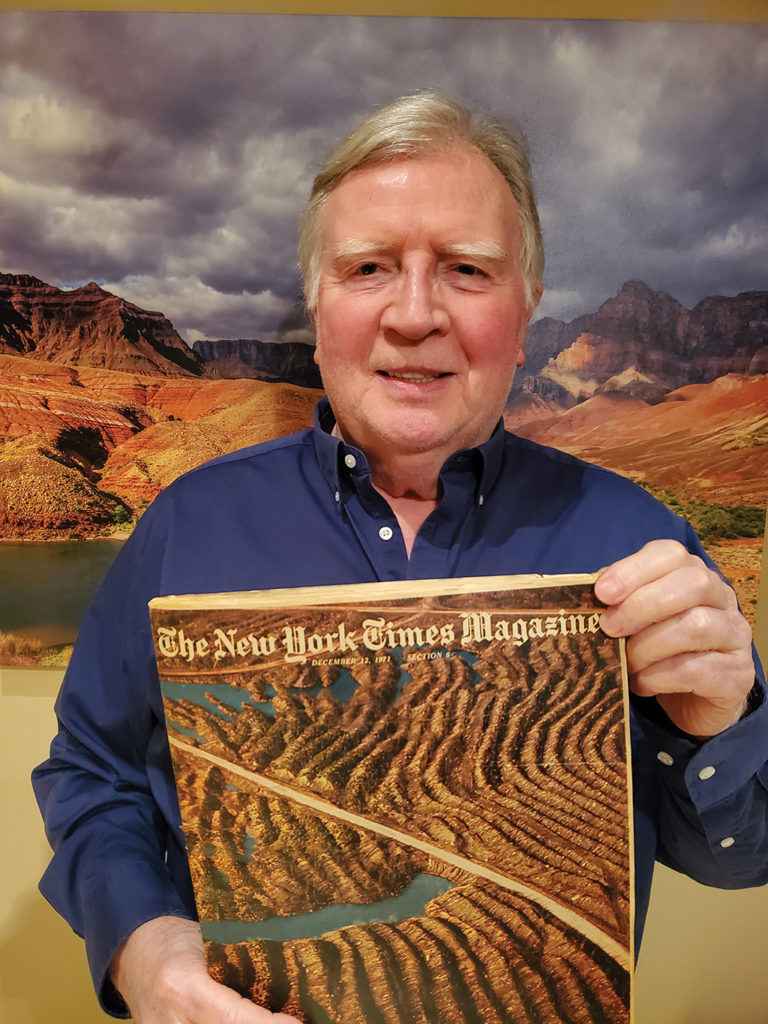

While still a student at Berea, I met New York Times reporter Ben Franklin, who was profiling the College as part of a series on Appalachia. When the Times magazine editors in 1971 were looking for a story about coal strip mining in the mountains, Franklin suggested I write it. It became a cover story, was read into

the Congressional Record by Sen. John Sherman Cooper and helped propel the movement for federal strip-mine legislation.

That same year, my wife, Sharen, whom I had met at ARC while she helped recruit nurses to the region, joined Mike Clark ’67, who was in charge of the Appalachian Program at the Highlander Research and Education Center in east Tennessee. Clark and I co-founded the Southern Appalachian Leadership Training Program that ran for 25 years, training community leaders to start economic development projects and to effectively make government responsive to their needs. One of the projects we supported at Highlander was Betty Jean Hall’s Coal Employment Project that won the right for women to work as highly paid coal miners.

I’m now convinced the solution to poverty is money in people’s pockets. What I have in mind is a universal basic income—“assured income” may be a better term—that is now being supported by policy wonks on both the right and left of national politics.

Jim Branscome ’68

So, half a century later, what policies and programs would I suggest to really help the Appalachian region? I’m now convinced the solution to poverty is money in people’s pockets. What I have in mind is a universal basic income—“assured income” may be a better term—that is now being supported by policy wonks on both the right and left of national politics. There have been small demonstrations of assured-income programs, such as in Stockton, Calif., which showed that a level of support did not lead to freeloading, but instead enabled people to sufficiently improve their opportunities to get full-time jobs. We should do a national demonstration of basic income support in the 60 counties of Central Appalachia.

A base level of income would allow young people to remain in the region, “refugees” who have left the region to return, and it would allow everyone to raise their income level to the point that they can concentrate their attention on revitalizing the region. At a time when climate change is raising sea levels, western drought and fires are threatening the growth of half of the nation’s fruits and vegetables in California, and the COVID-19 pandemic is demonstrating people can work from anywhere, it’s time to think about what revitalizing and repopulating the mountains could do not only for Appalachia but also for rural areas across the nation.

In addition, we need to recognize that Appalachia, while poor, pays much higher rates for social services than the rest of the nation—40 percent higher across the region. Through RIPmedicaldebt.org, which buys medical debt for a penny on each dollar, Sharen and I started an Appalachian campaign to pay off the $240 million of available medical debt primarily in Appalachia’s poorest counties. So far, $192 million of that debt has been relieved, people’s credit records have been cleared and they are now freed to use credit again for income support. While much of the national reporting on the region about how far behind we are economically still is negative, there are very exciting things happening in communities all over the region to get on a growth path. Recreation, revitalizing crop potential, alternative energy, broadband, restoring abandoned mine land with native trees and vegetation, and a host of other efforts are demonstrating mountaineers are pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. We need an income assurance program to put Appalachia on sound footing so we never again have to be called “an island of poverty in a sea of affluence.”

I’m proud of the influence you have had in support of Berea. I am a ‘68 graduate.

Thanks, Susan. I know you are from Tyner. Paul Chappell was also and was a good friend of mine in our class. This same issue of the Berea Magazine has an article about Tim Marema, the editor of the DailyYonder.com. Tim is from Annville and was a few years later than us in graduation.