Too Christian, not Christian enough

It’s not rare in America that a liberal arts college is church-affiliated. It’s also not rare that a liberal arts college used to be church-affiliated.

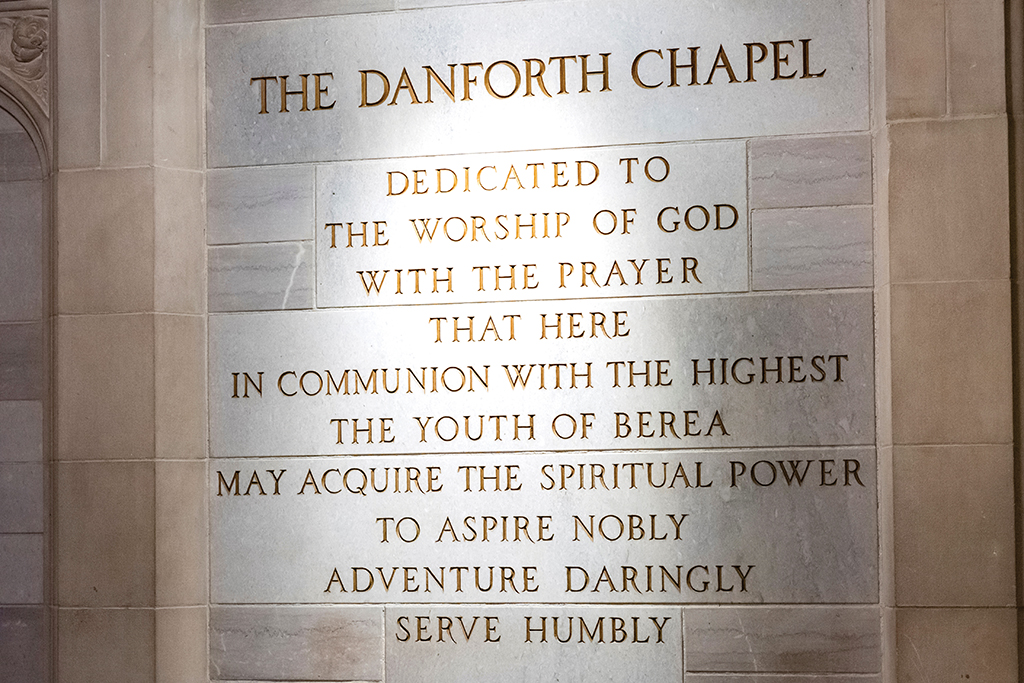

What do we make of a school, then, that is both “distinctly Christian” and explicitly, intentionally not church-affiliated?

For the uninitiated student, answering this question can be difficult. To a non-Christian student, Berea can seem “too Christian” for one’s taste. To the Evangelical, it can seem “not Christian enough.”

It may be surprising to students, too, that the College is perfectly comfortable with leaving this question up for debate. What matters more to the folks at the Willis D. Weatherford, Jr. Campus Christian Center is that students are accepted for who they are, that they are supported in their respective spiritual and academic journeys and that they learn from each other.

The principles of acceptance, support and learning have their roots in the College’s Christian founding by the Reverend John G. Fee, who was raised and ordained in the same Presbyterian tradition that spawned a long list of liberal arts schools such as Lake Forest, Monmouth and St. Andrews.

By the time John and Matilda Fee arrived on a ridge that would become Berea in 1853, they were no longer affiliated with the church due to a schism brought about by their stance against slavery. The disagreement would move the Fees to be critical of “sectarianism” as they built a new life, a new town, a new church and a new college they believed should be open to poor students regardless of race or gender.

This radical new stance came to be called “the cause of Christ,” rooted in “the gospel of impartial love.” Today, this gospel serves as the foundation for Berea’s radical endeavors.

The Gospel of impartial love

In the beginning, the environment John and Matilda Fee worked within was hostile to their views, which put them in physical danger. They leaned on scripture for guidance, specifically the egalitarian passages of the New Testament. Christ’s command that they love their neighbors as themselves both inspired their abolitionist advocacy and pulled them through a time of violence and crisis. Another verse, Acts 17:26, which in modern translation reads, “God has made of one blood all peoples of the earth,” reaffirmed faith in their mission to educate blacks and whites, women and men, together as equals.

That verse became the Berea College motto.

The Fees’ situation was one of a lone voice in the wilderness, not only opposed by many churches, but sometimes by other abolitionists, who opposed slavery but did not go so far as to advocate for the equality of the races.

“It’s hard for us to get our brains around that,” said Rev. Dr. Loretta Reynolds, dean of the chapel at the Campus Christian Center, who has served the College for the past 21 years. “For them to say blacks and whites, men and women should be in the classroom together, should sit at the table and eat together—he was going farther than most. He was radical.”

In forming the school, Fee was careful to impose a sort of separation of church and college by explaining Berea College was a liberal arts institution, not a bible college with the explicit aim of training pastors for ministry, though certainly some graduates might pursue that vocation. He was adamant, too, that the College not be associated with a particular denomination. “I think Fee was concerned,” Reynolds said, “that if you are connected to a larger entity like a denomination, then survival and being true to that particular organization becomes your purpose. So he said we’re not going to be connected. That left Berea to decide what it means to be founded on these very clear Christian doctrines but not having an external body telling us what it means in practical, day-to-day terms.”

What it means in practical, day-to-day terms has changed over the decades. The world the Fees inhabited is not the same as the world today, nor is today the same as 20 years ago. Chapel services, once required, are now a matter of choice, and students also have more choice around classes in religion. The inclusive mission has expanded from serving primarily Christian men and women of two races to people of all genders and sexual orientations and all races, ethnicities and faiths.

In other words: all peoples of the earth, including their various belief systems.

“We have had this challenge and privilege of being able in every age and decade to talk about, revamp, tweak and decide in each generation what it means to be a liberal arts college with a Christian identity,” Reynolds said. “What we’re deciding it means in 2019 is different from what it meant in 1960. I have always been impressed that even though certain elements have changed, those underlying qualities that were so important at the very beginning are still there: service, impartial love, the equality of all people. Those kinds of Christian values were there then, and they’re still here today.”

The Great Commitments and the great American experiment

Rev. Dr. LeSette Wright, Berea College chaplain, ministers from her office in Draper Hall, which was built to evoke Independence Hall in Philadelphia, her hometown. She’s new to the College and the campus community, coming to her current position from Boston, where she led the chaplaincy coalition that responded to the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013. Today, in her quiet Berea office, she tends to a small plant in the corner, musing about how Berea’s story is America’s story.

“The United States has said, ‘Give me your poor, your tired, yearning to breathe free,’” she recites, roughly, from the Statue of Liberty’s poetic inscription. “Berea has that same proclamation. Fee saw that our freedom is in God’s love for us. It’s the freedom we all yearn for, and Berea is radically different because it commits to walking alongside these populations. That’s the beauty of who we are.”

Like the U.S., Berea College has a constitution of sorts, adopted by the campus community in the 1960s and periodically amended, known as the Great Commitments. The preamble of this document reiterates the founding charter—the purpose of providing a liberal arts education to disadvantaged students is “to promote the cause of Christ.” The vision is predicated on inclusive Christian values advocating “the power of love over hate, human dignity and equality, and peace with justice.”

There are eight commitments, and each grows out of these values and serves as an articulation of them. If one were to summarize them in one sentence, it might go like this: A liberal arts education, commonly available only to the elite, is made available to students regardless of social status; working alongside one another in the labor program promotes equality and dignity; that dignity, because of our Christian understanding, is extended to everyone, regardless of race or gender; living together in that shared dignity means caring for oneself, each other, and the earth; and these values extend to the region beyond campus to Appalachian families as well.

“All the commitments are one package,” Reynolds adds. “If you look at them, the preamble lays the Christian foundation for all the other things. The concept of it being a Christian foundation permeating everything else can really be seen in all our documents.”

Reynolds notices the same pattern in the Wellness Wheel, a tool introduced to first-year students to help them adjust to young adulthood and college life in healthy ways.

Like with the Great Commitments, there are eight components dealing with emotional, financial, intellectual, occupational, physical, social, spiritual and sustainable wellness. Reynolds believes spirituality is both a component of the wheel and an underlying theme in all the components.

“When we talk about the Wellness Wheel,” she said, “I think of spirituality, not so much as a piece of the pie, but as the pie crust, supporting all the components and holding them together. If you’re talking about financial issues, there’s a spiritual component. How do I want to use my money in this world? For good or for ill? Spirituality is the underlying foundation that holds it all together. I believe that about the Christian commitment for the College as well. The Christian values of impartial love, service to others and loving your neighbor as yourself provide the foundation of all the commitments. Not everyone would agree with me. I know that.”

Everyone agreeing with each other isn’t really the point. The point is learning how to be with each other, how we treat others and ourselves, and leaving the details for each person to decide on their own. In that way, the gospel of impartial love is stridently democratic and fraught with tension.

“Berea is a microcosm of this nation because it commits to living in the tension of that,” said Wright. “There’s courage in coming to the table to become a community that truly understands the multifaceted nature of impartial love.”

Radical hospitality

At the Campus Christian Center, there is another name for the gospel of impartial love. It’s “radical hospitality.” In daily practice, it means all paths lead to an open door there, as well as a person who will welcome you in or walk alongside you, whoever you are.

In terms of programming, radical hospitality drives efforts to meet the educational, spiritual and social needs of students, staff and faculty of all persuasions through interfaith efforts. On Thursdays, at lunchtime, the Campus Christian Center hosts an interfaith program called Spiritual Seekers for discussions and speaker presentations to promote ecumenical conversation and engagement.

“I was a spiritual seeker myself in college, asking what I really believed,” said Rev. Dr. Jake Hofmeister, college chaplain, who comes to Berea from a Presbyterian background and chaplaincy work at Bellarmine University and Texas Christian University. Hofmeister runs the interfaith programming at Berea and supervises student chaplains of various faiths. “The whole process is something I want to help others explore when they’re at Berea.”

Berea students come from various backgrounds and have varied faith experiences in college. For some, mere exposure to other ideas causes them to struggle to come to terms with their own faith backgrounds. For others, they step onto a campus with little or no representation of their faith background at all. Either situation can be troubling for them. Without support, spiritual struggles can lead to academic and social struggles.

“In the classroom, students who have a particular religious identity, or an absolute truth claim, whether they’re Evangelical, Muslim or agnostic, can have a hard time because liberal arts education challenges those absolute truth claims and asks the student to wrestle with them,” Hofmeister said. “We want everybody to be fully themselves even if they have a particular view that excludes other truth ideas.”

Mohlatlego Makgoba ’19, who goes by Mo, served three years as a student chaplain. She came to Berea via South Africa with a faith background she describes as Christian with traditional African influences. Mo joined the student chaplains her sophomore year while pursuing an economics degree. She hosted small interfaith events in her residence hall, led mindfulness activities and tried to find ways to connect her studies to her faith. She also took it as her personal mission to assist students who, like her, were far from home.

“Berea doesn’t have any mosques or temples or orthodox churches that students might need to be okay when they are away from home,” she said. “We would provide transportation to Lexington, Louisville or Cincinnati where they could find a community for their faith.”

Providing what students need to be okay is a primary motivation for inter-faith programming at the Campus Christian Center, along with supplementing their education. While some may fear such interactions would be detrimental to faith, Mo describes the experience another way.

“The more you talk with different faith groups, the more you learn to appreciate your own faith,” she said. “That was integral to my growth. You have to love other people. Because of that you become closer to God.”

“Sometimes people have a hard time understanding how we can do all of that and still be the Campus Christian Center,” Reynolds said. “For us, we do that because we are the Campus Christian Center. We are called to this radical hospitality. We expect people to be their best selves, to support the commitments of the College, but our doors are open to everybody. The verse about accepting all people—it’s not just a suggestion.”

Hofmeister believes this openness—this radical hospitality—is a fundamental part of being a Christian modeled after Jesus’ own ministry. One example of this is the story of the woman at the well. In that story from the book of John, Jesus reaches out to a Samaritan woman, who was of a different faith.

“It’s highlighting the fundamental posture Jesus had was this radical hospitality,” Hofmeister said. “Jesus said, ‘I see that you’re from a different faith. Now go off and tell the world how I accepted you.’ His presence, his love, his ministry extended to anyone no matter what. And that’s how the woman evangelized. This person saw me for who I was, saw value in me, loved me even though I’m this, this, and this. Wow, that’s powerful.”