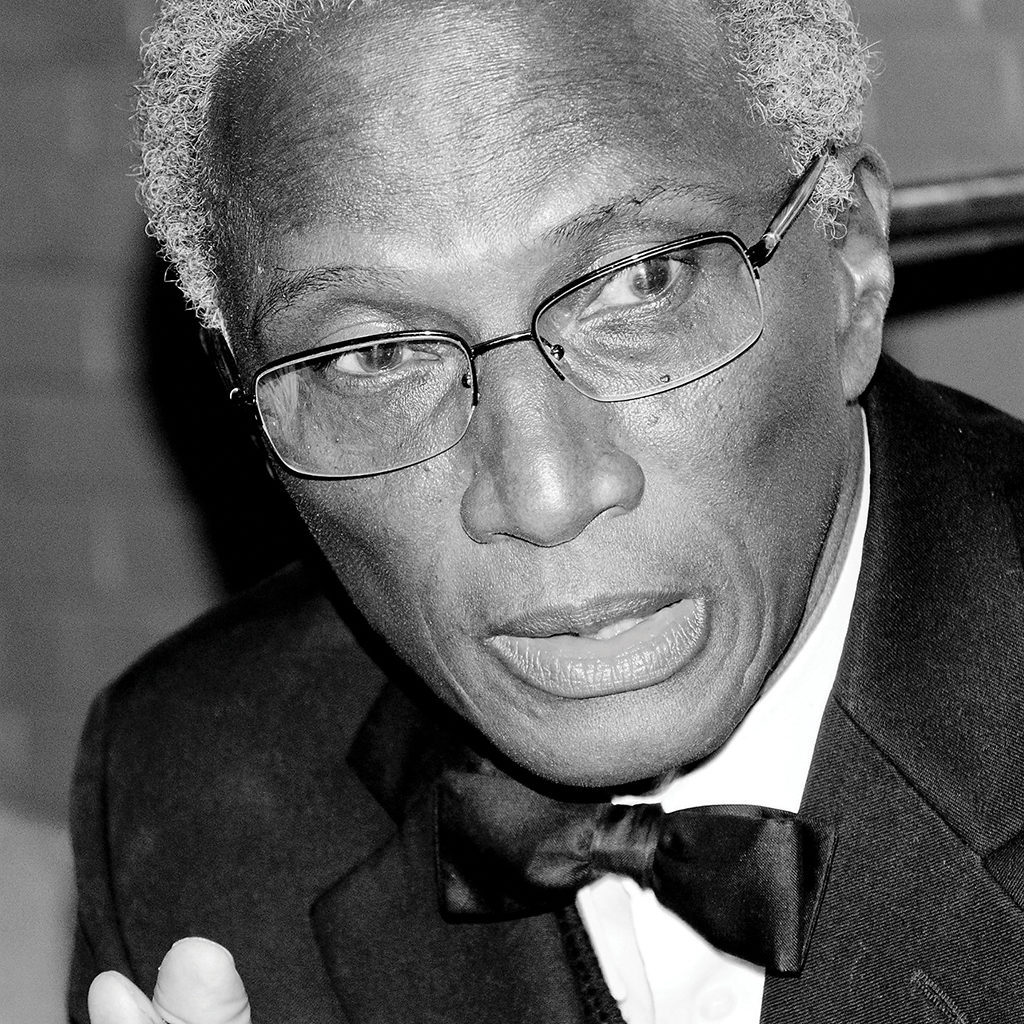

When the late Alex Haley, author of “Roots,” took William Turner to the Museum of Appalachia in Norris, Tenn., a short distance from the Haley estate, both men were surprised to find no mention of African Americans there. The proprietors of the museum in 1988 might have consulted Turner, a native of the coal town Lynch, Ky., and co-editor of the now classic “Blacks in Appalachia” (1985) as an authority on the subject who could confirm, that yes, indeed, Black people live there, too.

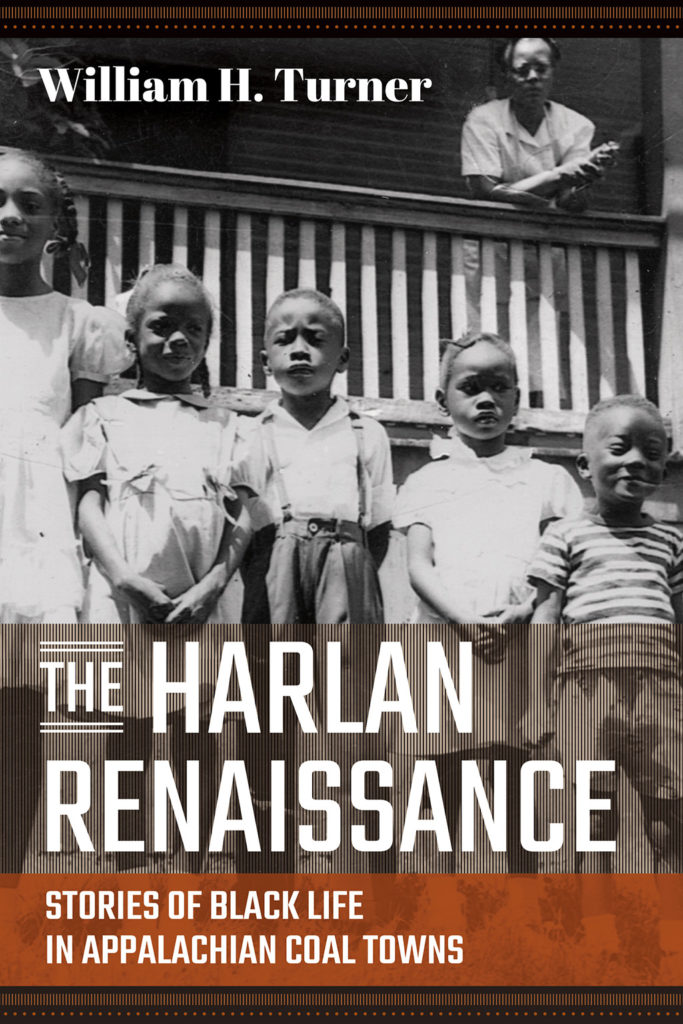

The seeming invisibility of this population, as well as Haley’s urging, inspired Turner to write a new book: “The Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in Appalachian Coal Towns.”

In this book, Turner, retired distinguished professor of Appalachian Studies at Berea College, takes readers on a tour of the Black community living in “the Cadillac of coal towns” in the 1950s and ’60s, where Turner was born and lived until he went off to college. It was a time and place that, in its heyday, was the “cultural and social epicenter” for Blacks in Appalachian Kentucky and Virginia.

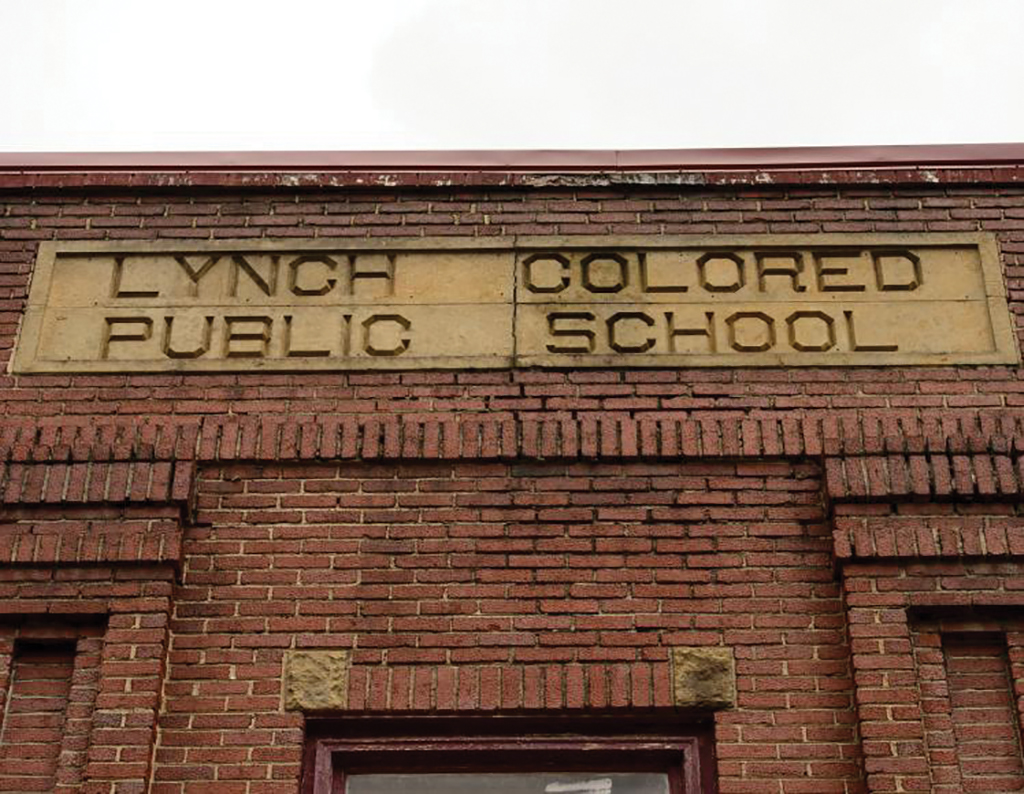

In Harlan County’s town of Lynch, named for a president of U.S. Steel, the company that founded it, readers are introduced to the clockwork regularity of the lives of Black coal miners and their families, whose existence was “up—just a tad—from slavery.” Though living, learning and worshipping separately from the white population, they eked out a standard of living that mirrored the white mining families. They collected the same paychecks, shopped at the same company store and made the same daily “mantrips” into the mines, where darkness and danger erased any differences.

At the base of Black Mountain, Turner deftly guides the reader through various gathering places—the pool hall, the family kitchen, an old oak tree—and introduces characters with nicknames like “Punkin,” “Junebug,” “Shootdaddy” and “Railhead.” Though much of the culture described is uniquely Appalachian, it carries a distinct sense of double-marginalization: the people reside within “subcategories and subgroups;” they are both Black and Appalachian, separated and isolated from the local whites, who themselves were separated and isolated from mainstream America.

In sum, “The Harlan Renaissance” chronicles a world of declension, and throughout the book there is a deep sense of loss as the author returns to the “home place” to find it a shadow of what it once was. Thankfully, through Turner’s vivid memories, the Cadillac of coal towns comes back to life with all its colorful, vibrant community. It’s a book only Turner could write, and without it, this slice of American culture would be lost forever.

The following are portions of a fuller interview with William Turner:

You published “Blacks in Appalachia” in 1985. What new light does “Harlan Renaissance” shine on this population?

The new light that shines may be reflected in something Alex Haley said, whom I met when Alex was on the board at Berea. He was introduced to me by John Stephenson, who was a president at Berea from ’84 to ’94. I sent Alex a copy of my book called “Blacks in Appalachia,” and when I saw him a couple weeks later, he put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Bill, don’t ever write any more BS like that again in your life. That’s purely for some scholars somewhere sitting up in an ivory tower who like to look at graphs and footnotes. If you want people to know something about Appalachia, if you want everyday people to know something about it, write it in a language that your mother will understand and won’t have to grab a dictionary or some Harvard-based encyclopedia to figure out what you’re trying to say.” So what I tried to do is have a new voice, a different voice in the book that spoke to everyday life issues of Black people in my hometown.

You say in the book that the late Berea College President John B. Stephenson was, besides your own father, the most influential person in your life. What was your relationship with him and why was he so influential?

In 1966, I was 20 years old. I had, for practical purposes, never been outside Harlan County in my life. I didn’t really have my eyes open to what was over that mountain there until I went to Lexington. When I went to register for my classes as a sociology major, I could literally follow the waft and smell of some pipe tobacco. They sent me to the office of this young professor named John Stephenson. I walked in there, and the next day I was smoking a pipe because I met this really cool professor who personified everything I thought a college professor should look like: the tweed jacket, the 1966 long hair, a beard. I took a class from John, and his wife Jane Ellen just literally adopted me. I started going in and out of their house for dinner a lot. John Stephenson was my muse. He was my enabler. He was the one who said, “Read this.” He was the one who, once when I was full of rhetoric in a paper I wrote for him—at the bottom of that paper, John wrote, “Oh, this is great. I’ve been looking for some paper to put at the bottom of my bird cage.” He wasn’t one of those white liberals who would patronize a little Black kid from Harlan County and pat you on the head and say, “Well, that’s about as good as you can do.” But John always said, “You can do much better than this, man. You owe it to yourself to be more disciplined.” So that’s who he was to me. My father was the same way.”

To quote from your book, “My life has spanned three generations of Black stuff becoming extinct.” There is a sense of loss throughout this book. The loss of community, the loss of the old oak tree that the men gathered around, the loss associated with mountaintop removal, the loss of Black educational traditions because of integration. How have you coped with these losses, and what is your hope for the future?

One way I’ve coped with and have tried to pass on to my own children and grandchildren is to follow the advice of Mark Twain: don’t let it make you mad, your losses. Don’t sit around and seethe in self-loathing and anger. I think Mark Twain said, “Anger [is an acid that can do] more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything onto which it is poured.” We always knew when you’re living in an extraction zone like we did—and my father used to say, “You know, coal don’t grow on trees like apples, buddy. Sooner or later, it’s all gonna be gone.” And it lasted about 100 years. You may remember in my book, I point out how when you come into the vestibule of our old church, First Baptist Church in Lynch, there was a little legend to the right, and every week they would change it because it had every member’s name and how much they put in last Sunday. Every now and then I would come to church and see somebody’s name scratched out. You say to your father at 10 years old, “Why did they take Mr. Freeman’s name down like that?” “Oh, they moved the other day.” That was a constant refrain in my upbringing. My story, my loss, wasn’t a solitary dance. Thousands and thousands of people experienced the same thing that I did. They’ll come back home [in May] for grandma’s grave on Memorial Day, which we used to call Decoration Day. They’ll come back just to put some plastic roses on that grave up the side of the mountain. Even though I live 1,500 miles from Harlan County, there’s 15 to 20 other people I know from Harlan County, from Pike County, from Letcher County, Bell County, who live right here in metropolitan Houston. So those networks are another way we manage that loss. Mama’s gone, Daddy’s gone, the kudzu has taken over where we used to play football, but you still have this heart filled with memories. And of course, the older you get, your memories are almost like food. If you don’t keep these memories, you die.

You say that Blacks in Appalachian coal camps were up “just a tad” from slavery. What do you mean?

Booker T. Washington, who had grown up in Charleston, W. Va., his autobiography was called “Up from Slavery.” So

I kind of use that as a springboard for thinking [about] African Americans coming in droves into the coal camps of [Appalachia]. My grandparents had been sharecroppers, you know. My grandmother had been born in Georgia in 1896, my granddad around the same time. They worked as sharecroppers—man that was just spelled a little bit differently than slavery. So even though people were emancipated from slavery in 1863, 1865, you’re still another 35 years [from] 1900, when they got out of that peonage, out of that servitude, Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and they got up out of there into the mountains of the South. Central Appalachia was a powerless kind of domestic equivalent of colonialism because everything was owned by somebody who didn’t live there. It was owned in Pittsburgh and on Wall Street. You live in a company house. You drink company water. You see by company lights and the company appoints the preacher that tells you everything that’s right. That’s the world of a coal camp. It was a totally controlled community.

If there is one essential message for readers of “Harlan Renaissance,” what would it be?

It would be what compassion, what care, what neighborly support these people gave each other that took them through the crucible of isolation in those towns. The fact that in the generation of my grandparents, it was not uncommon for people to have no schooling at all. But you can see also toward the end of my book where I look at the intergenerational mobility that took place. I look at the sons and daughters of my brothers and sisters, and I see one who graduated from Stanford, and I see another one who got a graduate degree at Clemson, and I see another one has a degree from the Patterson School of Diplomacy, and I see another one who did a postdoc at Duke, and I see one who went to MIT. And all these people, my daddy was their granddad. The message would be that our story is quite universal. We always knew there were people across the mountain who lived somewhere that had better houses than us and they had a better car than us, and they had a better view, if you will, than us, but they’re not better than us. And there was this big ole world—just keep going over that mountain—you’ll go over the mountain and say, “Daggone! I came over this mountain and there’s another mountain!” And you go over that one and, oh, man, there’s another mountain, east, west, north, south, a mountain. There’s always something that’s a challenge.

[…] College Magazine talks with William H. Turner about his forthcoming The Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in […]

[…] https://magazine.berea.edu/in-the-classroom/remembering-the-harlan-renaissance/ […]