It was the first week of March 2020, and the world was still right-side up. Thousands of people made their way through the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH), many of them in search of Dorothy’s ruby slippers or Lincoln’s top hat. What they found on the first floor’s Places of Invention wing of the Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Hall of Invention and Innovation was something different: a small troupe of Berea College students making brooms and weaving.

Until the pandemic, each year since Steve Davis-Rosenbaum assumed leadership of Berea’s Craft Education and Outreach Program (CEOP), students have taken spring break trips to demonstrate their skills. This year, they brought two vans, one for the nine students traveling to D.C., and another for their equipment, which included two traveling looms, one of which dates back to the 1930s.

They also brought a full broom-making set-up to celebrate a century of broom- making, 1920–2020. They invited museum visitors to make their own brooms, or to buy one, which people happily did.

“The staff at the NMAH were impressed with the professionalism, knowledge and skills of our students,” Davis-Rosenbaum said. “The visitors at the museum had a unique experience learning to make craft and about the rich history of Berea College.”

This was their first appearance at the Smithsonian, an event that capped off a weeklong sightseeing tour of the diverse crafts and arts of many different cultures. To organize the event, Davis- Rosenbaum reached out to Christopher Wilson, NMAH’s director of experience design, who specializes in living history, or performance-based programs, an approach he brought with him from the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan.

“We try,” Wilson said, “for all our programs to be a kind of bridge between people and U.S. history, to bring people together—people who don’t know one another—and use history to get them talking with one another and understanding one another more. We do that through a variety of activities, like theater programs, but also with hands-on activities.”

When Davis-Rosenbaum contacted Wilson about students doing a demonstration at the Smithsonian, Wilson was quick to understand its value. The spring break 2020 visit would be a pilot program, a precursor to developing summer internships for Berea students, though the pandemic has postponed that step.

“We had great feedback,” Wilson said. “It’s fascinating when you see a real expert at work. One of the keys is being able to demonstrate that expertise in a way that comes through to the audience. I think that was fascinating for people how some of these crafts were performed in the past and what they meant. The products they were producing were just beautiful.”

The two-day demonstration of traditional Appalachian crafts made an appearance to an estimated 24,000 visitors, many of whom had their own stories of visiting Berea College or a family connection to the history. One of those people with a special connection was Wilson himself. Though he hails from Michigan originally, his mother’s family has roots in Kentucky, and his great great great grandparents lived in Berea.

Though the family lore is a little shaky regarding things so far in the past, Wilson’s account and Richard D. Sears’ book “A Utopian Experiment in Kentucky” reveal that Wilson’s ancestors, Reverend Anderson Crawford, his wife Caroline and their 15 children lived on Center Street, which, in its original formation housed Black and white families on alternating plots. Reverend John G. Fee, Berea College founder, had recruited Reverend Crawford from nearby Camp Nelson as part of his mission to bring more Black preachers to Berea. His mission from the Freedman’s Aid Society of Cincinnati was to seek out half a dozen preachers, but Civil War veteran Crawford was the only one Fee was able to recruit. Between children and grandchildren, Anderson and Caroline’s progeny attended school in Berea from the earliest days until the Day Law segregated schools in Kentucky in 1904.

Stories of connection like Wilson’s to Berea are what these live demonstrations are all about.

“The Smithsonian is in a position, as a trusted institution in our country,” Wilson said, “to break down the bubbles in which people live. If we can get people to talk with one another, engage with one another and understand and respect one another’s backgrounds, then we can make a more just and compassionate world. I think this program was a really good example of how that can happen, using a partnership between the museum and the College.”

In collaboration with the Berea College Office of Internships and Career Development, Davis-Rosenbaum and Wilson had set up two internships in 2020 at the NMAH to continue craft outreach and education there, but this effort had to be cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Davis-Rosenbaum and the museum hope to work together to rekindle this effort and send the first Berea College interns to the Smithsonian in summer 2023.

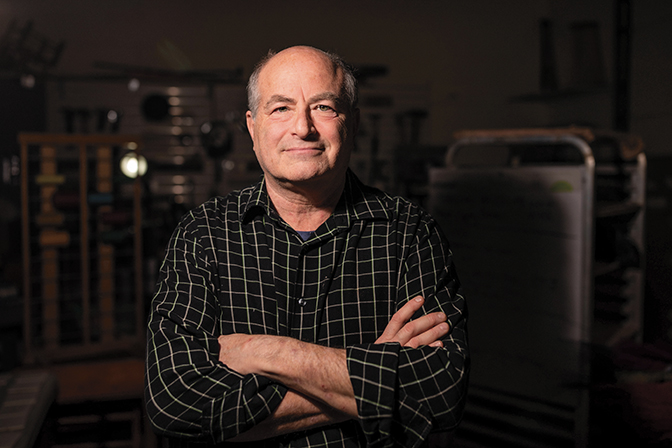

The Potter’s Tale: Steve Davis-Rosenbaum

If you ask the right question, Steve Davis-Rosenbaum, head of Berea’s Craft Education and Outreach Program (CEOP), will note the presence of all 10 of his fingers.

That’s because in a previous professional life Davis-Rosenbaum taught language to chimpanzees at Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta, Ga., a job where keeping all your digits in tact was not a guarantee. In fact, says the San Francisco native, the risk to his appendages was a primary motivator for seeking a career change.

“As the chimps got bigger, working with them became more dangerous,” he said. “I had to decide to stay and go to graduate school or change careers.”

That transition, in the 1980s, led the former biology major to follow his passion for ceramics, which he’d had experience within his undergraduate years at Lewis & Clark College as a way of balancing out the hard sciences. Even while working with chimps in Atlanta, Davis-Rosenbaum continued his pottery work by joining local pottery groups. He went back to school at the University of Georgia, earning his Master of Fine Arts degree in ceramics, and when he finished, he was hired by Berea College as the resident potter in 1986, a position he held for three years.

“That residency,” he said, “launched me from graduate school to becoming a really accomplished potter. It gave me the time to focus on my work and assist in managing the ceramics studio.”

Davis-Rosenbaum left Berea in 1989, and for the next 23 years, he ran a pottery business and taught art and ceramics, including a nearly two-decade stretch as associate professor at Midway College in Midway, Ky. His arc bent back to Berea in 2012, when he was hired to direct the College’s newly created CEOP, a program focused on promoting the craft traditions of Appalachia in underserved schools and communities.

The CEOP works mainly in nearby Appalachian county schools, helping teachers integrate craft into their curriculum. The program brings traditional fibers for weaving, broomcorn, ceramics and some metals for use in the classroom. The community service program of Student Craft meets the College’s Eighth Great Commitment: to engage Appalachian communities, families and students in partnership for mutual learning, growth and service.

“We work collaboratively with teachers who want to integrate customized craft workshops into their curriculum,” Davis-Rosenbaum said. “CEOP provides resources and expertise to non-art teachers in different disciplines including Appalachian heritage, writing, science and humanities by providing hands-on experiences not accessible in schools. The most popular workshop is ceramics, as most schools do not have access to equipment and supplies needed. Ceramics projects include units on American Indian pottery, art history and the Appalachian tradition of making.”