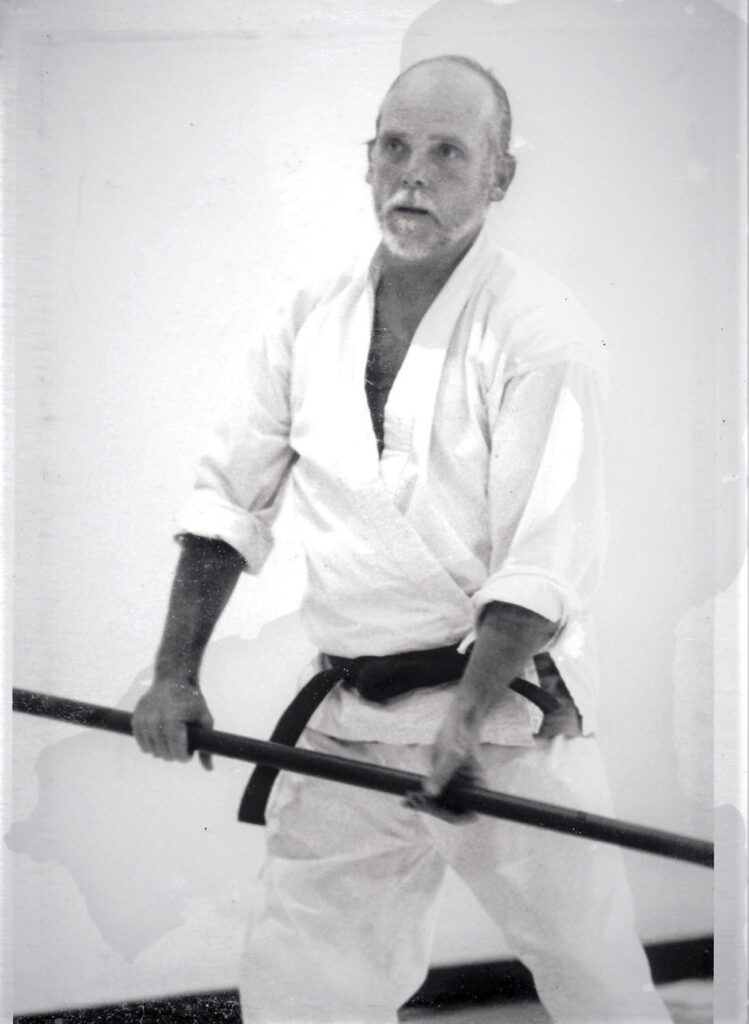

Dr. Thomas Boyd was known for his fiery, tell-it-like-it-is personality, his tweed coats with patches at the elbow, and a voracious appetite for reading. A scholar-activist with strong opinions and even stronger convictions, Boyd, as the chair of Berea’s sociology department, impacted the lives of hundreds of Berea students from 1977 until his retirement in 2006. His fervor for social equality, service to the most vulnerable populations and sustainable living taught those around him how to better the world in which they lived.

No place to call home

Boyd was born in Kenton County, Ky., in 1942, the only child of a World War II Navy man. After his father returned from war, he switched between jobs, moving the family all over the Midwest for years. They didn’t have much money, and with the constant moving, Boyd struggled to form friendships or roots. After attending high schools in Kentucky, Ohio and Illinois, Boyd graduated and entered Wabash College in Indiana in 1960.

“Wabash was a very expensive school—luckily, I was their contribution to social mobility; but I did have to work,” Boyd said in a 2005 interview with the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History.

In the summer, Boyd worked with his father at a woodcraft camp at Culver Military Academy. Though he thought he wanted to be a doctor, he found psychology to be more his calling, and he minored in economics and English. During his last year in college, a young man wearing a tweed jacket, jeans and work boots spoke at a chapel service about getting out into the world and knowing what was going on. It was Boyd’s introduction to the Peace Corps, and he was intrigued.

“He didn’t say this was a career move,” Boyd recalled. “He said this was a personal move. This was something that you did to check your character and to learn.”

As graduation neared, Boyd had several options before him, including Peace Corps, Naval Officer Candidate School (OCS), Marine Corps OCS, a position at Goodyear Tire and Rubber, and he was on the waiting list at Ohio State University’s business school. But for Boyd the answer was clear—he would choose the Peace Corps because it offered the biggest adventure.

“There was that great feeling that when I got accepted and then when I got on the plane to go out there, that the world was my oyster,” Boyd said in the 2005 interview. “I was doing something that none of these guys at Wabash was doing, even though they had finances and they had jobs or law school or whatever. I really felt that I was in a wonderful adventure.”

After going through difficult training in New Mexico, Boyd made the final cut from 50 to 18 individuals chosen for Peace Corps assignments in 1964. He found himself assigned to physical education, teaching sports programs in Colombia to orphans and street kids. His time in Bogotá was not the typical Peace Corps involvement, but rather a rollercoaster of experiences that had him serving in multiple locations. He was essentially on his own, living in a two-room house with an eccentric old lady bouncing among Bogotá orphanages, schools and other random places throughout Colombia. During this time, he contracted tuberculosis, dysentery, lice, intestinal parasites and bad rashes. Lack of access to clean water and less-than-favorable living conditions made Boyd miserable but not homesick. The friendships he formed with his Colombian colleagues and neighbors learning to play the “tiple,” a 12-stringed guitar-like instrument, playing chess and going to bars made the experience one he’d cherish for a lifetime.

When it came time to leave the Peace Corps, Boyd met Monte Koppel, an American professor from the University of Puerto Rico, who became one of his mentors. He encouraged him to apply to a master’s program at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, Netherlands. In between completing a national development graduate diploma course and obtaining his master’s degree in social sciences, Boyd worked summers in the U.S. with the Encampment for Citizenship in Washington, D.C. and New York City. He was constantly surrounded by people from various cultures and was one of only three Americans in his master’s program in the Netherlands. After completing his degree, his connections in the Netherlands helped him obtain a position in the Development Studies Institute of the University of Cape Coast in Ghana, West Africa, where he conducted research in villages and taught sociology. He also made close friends and grew to love the people and places of Ghana. After three years, when his position ended, he considered staying in Ghana, but instead, he returned to the Netherlands.

“I get on a plane, I say goodbye to my African friends, and it’s really hard,” Boyd recounted in his 2005 oral history interview. “I wept when I left Colombia. I didn’t weep when I left America. I wept when I left Colombia, and I wept when I left Ghana.”

At that point, Boyd realized he was “a different kind of American.”

“I developed a philosophy that the Peace Corps taught me that if people lived there and I’m a person, I can live there,” he said. “I don’t need to, you know, try to think about what I’m missing or whatever.”

This was the beginning of Boyd’s belief in simple, sustainable living—realizing that people don’t need material things and wealth to be happy.

After another year at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, Boyd applied to Cambridge University, where he spent three years earning a Ph.D., but not feeling like he really belonged there. Though he enjoyed the intellectual rigors, he didn’t have the money other students did to travel and entertain themselves—he didn’t cry when he left Cambridge, he said.

Putting it into practice

It was now 1976, and Boyd’s parents’ health was declining. He decided to move back to the U.S. to help care for them. He wound up placing his parents in a retirement home in Ohio, took a job in West Virginia and decided he would try to do in Appalachia what he had done in developing nations. Boyd worked for a year at West Virginia Wesleyan College, but the school wasn’t a good fit for him, so he turned his sights to Berea College. He applied (for the second time) for a position and was hired as an untenured assistant professor. Boyd rolled into Berea for the first time on the same day Elvis Presley died, August 16, 1977, and it’s where he called home until his death 42 years and four days later on August 20, 2019. Boyd identified with and loved Berea because he said it was a working-class college.

“He definitely supported opportunities for working-class students because that had been his history, too,” said Dr. Jackie Burnside ’74, Berea sociology professor.

“He was very devoted and cared deeply for students,” added Joan Moore, a former nurse practitioner at Berea College Health Services and Boyd’s long-time friend. “He identified with where they were coming from and their backgrounds.”

According to Dr. Jill Bouma, chair of Berea’s sociology department, Boyd believed in putting academics into practice. He started a course on applied sociology because he wanted sociology to be something one could apply to organizations and communities to improve society.

“Before service-learning really had a name, or became a sexy thing to do, he was doing service-learning,” Bouma said. “He was taking students into the countryside. He had summer projects where he had them working in Appalachia.

“He believed in evidence-based arguments, the use of data to build a case and to explain the social world,” Bouma continued. “He believed in deep research and research for the common good. He took his skills and applied them to the world through his work in Appalachia and Ghana—it was not just local, he had a global view as well.”

Boyd started Berea’s Sociology Club, which grew from a highway beautification project in the early 1990s where students adopted part of a highway and picked up trash. He also taught some of the most innovative short-term classes, Burnside recalls. In one course, students were responsible for a fictitious family. During the month-long course, students had to find out what social services were available to the family and what was involved in connecting the family to those services. In particular, they looked at housing and focused on issues of homelessness. As part of the course, students built cardboard campouts on the lawn of Union Church and spent a day and night living in appliance boxes to get a taste of what it might be like for these families.

He also taught a short-term course on simple living, Bouma remembers. “It came from a deep belief in how you fight inequality,” she said. “You don’t need that much individually. He didn’t aspire to big houses and fancy cars. He was very anti-materialistic.”

He had high standards; he pushed students to do their best. … He got them thinking about things that just drew them in.

Dr. Jill Bouma

“He had high standards; he pushed students to do their best,” Bouma added. “He was just funny. He taught 8 a.m. classes, and you could hear students laughing next door. He got them thinking about things that just drew them in.

“It was inspiring to know someone who truly lived their values,” Bouma continued. “He believed in what he taught. He believed in social change. He was trying to fight and contest the severe inequalities we have in this country.”

Boyd’s impact wasn’t reserved only for those on Berea’s campus. His beliefs and work spilled out into the community as well.

“He loved his teaching job and took it seriously, but he loved the community, too,” said Pat Wagner, one of Boyd’s long-time friends.

In addition to teaching, Boyd served as the director of Kentucky River Foothills Community Action Agency, a volunteer firefighter with the City of Berea, a supporter of and volunteer for Habitat for Humanity, a board member of White House Clinic and a board member at Pine Mountain Settlement School. He cared about the impact of school consolidation in rural communities and was an advocate for children in Head Start.

Boyd’s care for low-income, vulnerable populations fueled much of his community involvement, especially when it came to housing. He was instrumental in helping create the New Liberty Homeless Shelter in Richmond, Ky. The shelter has six two- and three-bedroom apartments equipped to handle homeless families with children.

For all of his efforts, Boyd received the Elizabeth Perry Miles Service award in 1991, which is given to Berea faculty members who exhibit significant service to the Berea-area community that goes above and beyond their usual job and enhances community life.

In addition to all this work, Boyd still managed to affect change in the global community as well. The summer before coming to Berea, he worked in Zambia as a consultant with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. He worked with Habitat for Humanity in Peru, spent sabbaticals in China and England and completed a Fulbright fellowship in India.

“I connect with the world in a different way,” Boyd said in his 2005 interview, noting that depending on the kindness of strangers in other countries brought to mind Berea College founder John Fee’s egalitarian mission. “It’s not like America is on top and the rest are down. We can learn a lot, as I did, from other cultures and other people.”

Leaving a legacy

The profound impact the Peace Corps had on Boyd’s life was part of why he, along with several former Peace Corps volunteers he met in the Berea community, created the Eastern Kentucky Returned Peace Corps Volunteers group. Lowell and Pat Wagner, Phil Curd and Ted Kay bonded over their transformative Peace Corps experiences and initially used a national mailing list to find more former Peace Corps members in the area. Their first meeting was on Berea’s campus with about 25 attendees. The meetings continued for years at Camp Andrew Jackson with potluck meals, big tents and activities for kids.

“It grew to nearly 100 people; our kids grew up together and got to know each other,” said Lowell Wagner. “We would swim, tell stories over drinks and do native dances from the countries where we served.”

Eventually this group became more organized and expanded to include all of Kentucky as the Kentucky Returned Peace Corps Volunteers, of which Boyd was a co-founder and board member.

“Phil Curd, Lowell Wagner, all of those returned volunteers…when we get together, we don’t talk about our investments, we don’t play golf,” Boyd said. “We talk about world peace, we talk about international affairs, and we laugh and we do those things.”

Laughter mixed with seriousness and a focus on what really mattered made up Boyd’s personality.

“When I think about Tom, I think about how he was curmudgeonly but also had a real softness about him,” Pat Wagner said.

He was straight-forward, clear, funny, incredibly organized and curmudgeonly. You never doubted where he stood, and I loved that about him. When he was in your corner, you had a really strong advocate. … He was incredibly supportive.

Dr. Jill Bouma

“He was straight-forward, clear, funny, incredibly organized and curmudgeonly,” Bouma agreed. “You never doubted where he stood, and I loved that about him. When he was in your corner, you had a really strong advocate. That was true for organizations, students and faculty. He was incredibly supportive.”

Even with his tremendous education and his job with the College, Boyd truly was a man of the people, always looking to make people and programs better and more successful, said Adriel Woodman, who worked with Boyd through Kentucky River Foothills and Head Start.

“He was such a character and so generous,” Woodman said. “There was no one like him, and there will never be another.”

His quirks carried right on through to his retirement. “His essence was super fiery,” said Amy Harmon ’99, Berea’s director of planned giving. “He drank brandy and smoked a pipe every day.”

No longer being in the classroom freed Boyd up to focus on his budding passion—wood carving. It was a skill he had picked up years before, but after retirement he honed the skill and created hundreds of carved pieces that were placed around his home, given to friends and displayed at the Berea Arts Council. At his Crescent Drive home, the same home he moved into in 1977, his belief in simple living became even more evident.

“He said, ‘If I can live on $2 a day there, I can do it here,’” Harmon recalled of Boyd talking about his time overseas, especially in Colombia. “He just realized he didn’t need that much. Nothing he had was new. He was really frugal.”

Because Boyd had subscribed to this simple-living mindset most of his adult life, he was able to use his finances to impact many organizations. Most who knew Boyd knew his generosity. As retirement progressed and his health waned, he began working with Harmon on a gift to Berea College. Not only had he given to various organizations and programs through the years, he also had maxed out his contributions to his retirement account.

“He realized how hard it was for students to go to graduate school, and he liked the direction the Sociology department was going, so he wanted to create graduate scholarships for Berea students,” Harmon explained.

When he first began exploring the idea, Boyd told Harmon his gift was probably small for Berea, but he wanted to do something to give back, she recalls. But when it was all brought to the table, Boyd’s retirement savings alone totaled more than $1 million. Since his passing, his gift stands as the largest to the College by any faculty or staff member. It established two endowments, one for graduate scholarships and a smaller one for discretionary funding for academic needs of the sociology department.

“I hope folks will not think any more (or less) of me because of my abnormal savings rate,” Boyd wrote in the public disclosure of this gift. “The financial basis for this gift was not really a conscious decision; it was simply due to the fact that my consumption reference group was the Colombian peasants who I associated with right after college, plus my parents raising me on short rations. No philanthropist in me—I’m just a financial curmudgeon who didn’t want to be a card-carrying member of a consumer society.”

Named the Thomas A. Boyd Graduate Scholarship in Sociology, Boyd’s bequest allows both sociology graduating seniors and sociology alumni to obtain scholarships for attending graduate school. It was important to Boyd that the scholarship be open to alumni as well because many in the department pursued other endeavors between finishing undergraduate degrees and attending graduate school: Burnside was in the U.S. Army and Boyd, Bouma and Dr. Andrea Woodward all spent time in the Peace Corps.

Over my 30 years of Berea teaching. I saw many, many, many examples of the worth of our admission policy for students with financial need coupled with great academic drive and potential. Berea was a blessing for my life as well as [these students’ lives].

Tom Boyd

Harmon recalls how emotional Boyd was when he saw his name on the scholarship for the first time.

“He cried so hard,” she said. “It brought him to tears to see something in his name, and I think it was the impact he hoped to have in this life. He wanted people to see what is possible when you live frugally and choose to be different.”

For Boyd, what started off as wanting to take on the biggest adventure life had to offer turned into a way of life and looking at the world around him. His choices and experiences changed his own life and gave him the opportunity to impact the lives of countless people who crossed his path at Berea and all over the world. And that impact will extend to dozens of students who will never know this fiery, fun and fervent professor in class but whose educational futures are propelled by his generosity.

“Over my 30 years of Berea teaching,” Boyd said in an email to Harmon last spring, “I saw many,

many, many examples of the worth of our admission policy for students with financial need coupled with great academic drive and potential. Berea was a blessing for my life as well as [these students’ lives]. The College provided a cause of service for me. It was much more than just a place to teach sociology—it is an outlet for economic and social justice in America.”

Dr. Boyd was my favorite professor at Berea. I wish I’d told him that. He was a phenomenal teacher and I benefit from his clear thinking to this day. I knew he’d lived all over the world b/c he talked about it a lot but I had no idea the sheer scale of things he was involved in. I’m so proud to have known him. Hats off to you, Dr. Boyd!