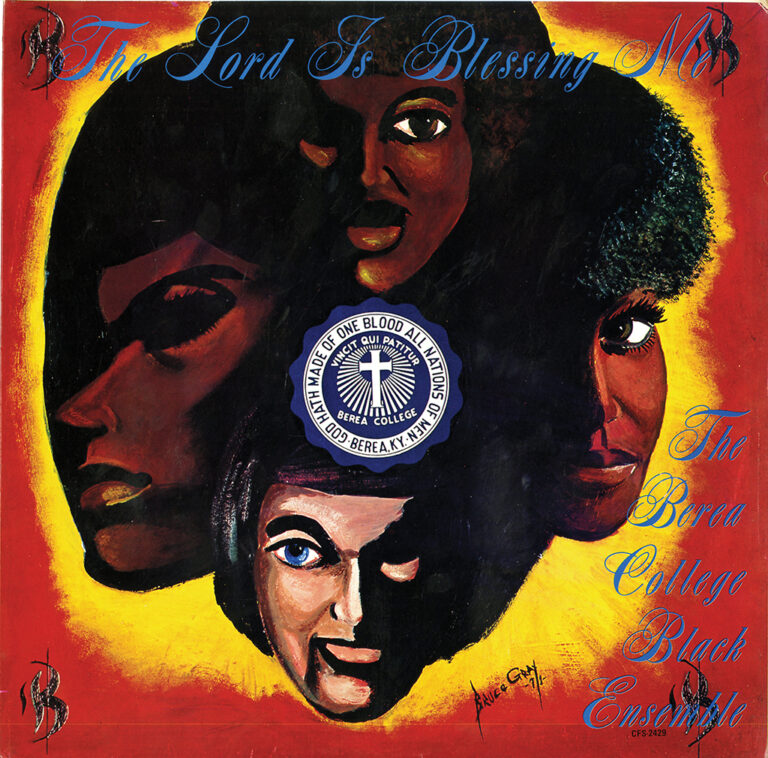

The Berea College Black Ensemble recorded its first album, “The Lord is Blessing Me,” in 1971. The cover art was created by Bruce Gray ‘73 to capture the group’s vibrant and uplifted emotions.

What is now a Berea College institution, the Black Music Ensemble—with 80 members who tour all around the country—was born 50 years ago out of a small group of students yearning to hold on to their spiritual heritage and share it with others.

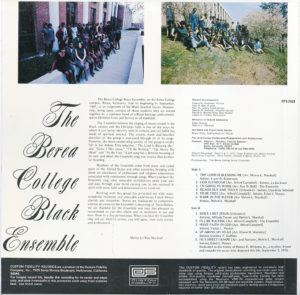

Just two years later, the group recorded an album for distribution, and for a time, the album was for sale in the campus bookstore. Over the decades, albums were given away, locked safely in basements, lost, or placed in the archives of the Hutchins Library, waiting for a new generation to discover what is now an enduring Berea College artifact. What it reveals is the heart and soul of a few dozen young people looking bright-eyed toward a more promising and inclusive future.

In 1969, there weren’t many black students on campus, even though Berea College was reintegrated in 1950 when the Day Law prohibiting integrated education in Kentucky was revised. Many of the black students who were present, though, were advocating for change. They established the Black Student Union, petitioned the administration to resolve the absence of Black faculty and staff, and banded together to celebrate their history. At stake also was their spiritual lives—the chapel services and the music of the chamber choir left them longing for the music with which they had grown up. In the spring of that year, Charles Crowe ’70, now a Berea College trustee, suggested they form a singing group.

In the summer that followed, the College administration began searching for an African-American counselor who could better serve the students’ needs. They found Melvin Marshall in Atlanta, who would join Berea in the fall of 1969.

“My family was the only black family on campus,” he relates, “and I was like those students’ other daddy.”

Marshall and his family hosted Sunday dinners at his home, a throw¬back to what the students had been used to growing up. Though he didn’t have a professional music background, he had been a gospel singer and had directed choirs at other schools. Marshall signed on quickly to the idea of forming the Berea College Black Ensemble, which would rehearse while the students were at his home on Sundays.

“I thought the Black Ensemble would be something that could bring the students together and provide them an opportunity to exhibit their musical talents,” Marshall said.

“We were all away from home,” said Debbie Leeper (Gray) ’74, who sang soprano in the group, “and this ensemble on Sunday gave us a sense of unity and brought us back together like we remembered from going to church in the South. It gave us a sense of belonging to a loving and caring family.”

Listening Today

The Berea College Black Ensemble lives on today as the Berea College Black Music Ensemble and includes 80 multiracial members from the College and community. They perform spirituals, gospel music, West African songs, anthems and other sacred music by African-American composers. Listen to songs from the 1971 “The Lord is Blessing Me” album.

Elaine Wormley Allen ’73, who would become a pianist and arranger on the album, came to Berea in 1969. Having learned to play by ear from her father, Elaine found an old piano in her residence hall and began to play a familiar church tune. Another student, Gay Nell Bell (Duckett) ’71, proclaimed that song was exactly the sound the group was looking for and invited her to Marshall’s house to play for them.

Allen describes herself as a shy young woman from West Virginia, lacking confidence in her ability to truly provide accompaniment. But at Marshall’s house that Sunday, she played for them anyway.

“I played a few songs,” she said, “and Melvin said, ‘That is it!’ I said, ‘That is what?’ He said, ‘We’re going to put together a group called the Berea College Black Ensemble, and you’re going to play the songs.’”

The group created a list of songs they knew, and Elaine would play or learn them. She alternated piano responsibilities with Bell, Willene Hairston (Moore) ’71 and Sue Hairston (Jones) ’72, among others. Responsibilities were shared liberally among the group, with Crowe as the leader and organizer, and directing duties falling to whichever student taught a song to the ensemble.

By 1970, the group boasted 50 members and was touring churches and other venues. Marshall invited Alfred Campbell, a church choir director from Atlanta who is listed as an arranger on the album, to help prepare them for performances.

“Alfred Campbell made us more of a professional group,” Gray said, “and gave us some ideas on how to present ourselves when we went out on performances.”

The album, with the title “The Lord is Blessing Me,” was recorded over two days in April 1971 in Gray Auditorium by Custom Fidelity, a company that recorded many choirs at that time. Marshall directed the group, except when he performed with them, at which time a student, Edsel Massey ’72, took over the directing duties.

Marshall explained that the songs were chosen because of the meaning they had for him and the students and how they represented the struggles of Black people at the time. “‘Wade in the Water’ really had meaning,” he said. It meant that “if you don’t get into the action, you’ll have no effect. You have to get into it and get involved.”

The group recruited Bruce Gray ’73 to produce the cover art, which he describes as “expressionist realism.”

“I was trying to capture the emotion we had at the time, which was vibrant, uplifting. People were trying to move forward. The situation at Berea was wonderful for everybody. You were treated as an equal. A lot of the students were coming from southern areas, so that made it extremely special. The cover was a project of love that tried to capture a sense of who we were and what we were doing.”

“It was the most blessed situation,” echoed Leeper (Gray). “It was unbelievable because we were a small little ensemble. Berea gave us the platform and the motivation, made us feel like we could do anything. It gave us the confidence to sound like we sounded.”

The Grays joined the military after leaving Berea College, which required them to move often. The unfortunate result is that the album was lost over time. “My children don’t believe that this ever happened,” she said.

Allen has kept her copy in a designated trunk all this time. Back in the 1970s, she sent a copy to her brother in West Virginia, a radio preacher, who would play “He’s Sweet I Know” from the album at the top of every broadcast.

“For me,” she said, “that was the highlight of my education at Berea. It is something that has been with me since that time. This album does now as it did then: it gives me validation. It is a part of history, a legacy I can leave for my children and my race.”