At first glance, the minutes of the Sept. 7, 1892, Berea College Board of Trustees meeting seem unremarkable. President of the Board, Rev. John G. Fee, opened the gathering with the singing of hymns and praying. Then the scribe listed those present and the treasurer’s report.

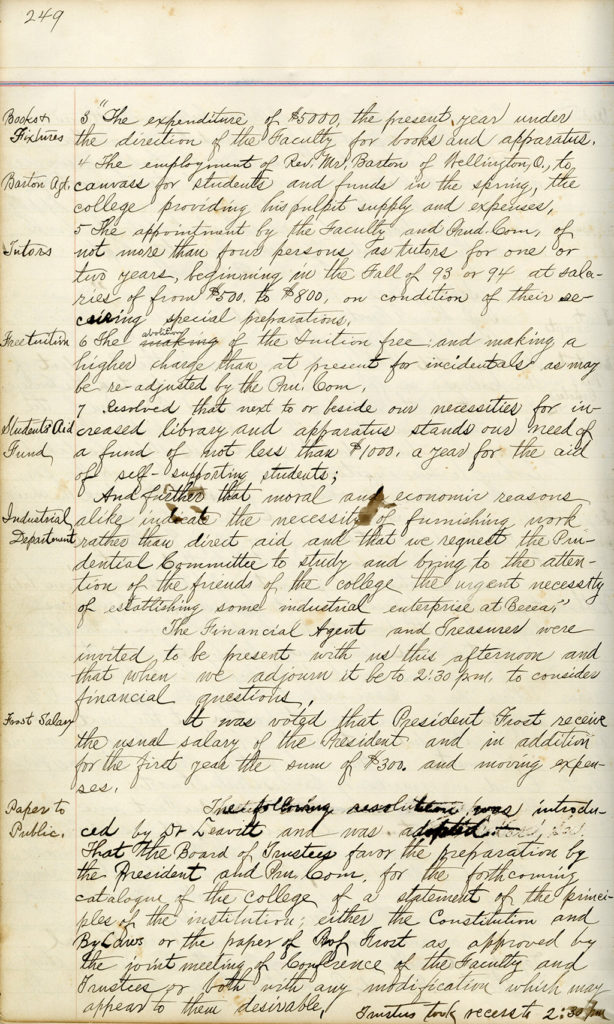

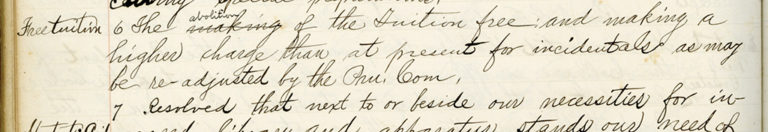

But item No. 6 in the hand-written notes invites pause. With a single sentence and the simple heading “Free tuition,” the Trustees made an historic and visionary decision: they abolished tuition for all students. It is a commitment that the school has upheld, come what may, for 130 years and has become a foundational part of Berea’s ability to enable students with limited means to attend college.

At the time, it was not a large fiscal decision. In promotional materials from 1871, Berea already promoted itself as a low-cost option for college. Tuition was just $1 per month (approx. $20 today), and total costs for careful students were not more than $130 per year (approx. $2,700 today). After the tuition-free guarantee, an 1894 advertisement estimated the annual cost for expenses at $100 per year (approx. $2,100 today).

It’s really never a good time for a college to contemplate reducing revenue, but the timing of this moment seemed particularly poor. The minutes of the same trustees meeting report a plea from the librarian for $200 to purchase library books. “Not a volume could be purchased last year,” the minutes state. But the Trustees held firm, “Special solicitation of funds for the library must not be allowed at present to detract attention from the immediately pressing need of general endowment.”

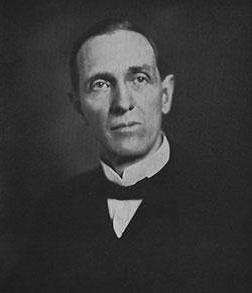

Berea was in financial straits. As school President William G. Frost wrote in his June 1893 Synopsis of President’s Report, “our struggle to extinguish the debt and choke the annual deficit is yet to be made.” Yearly shortfalls had brought the school’s total debt to a discouraging $30,000 (approx. $639,000 today).

Berea had also lost one of its primary means of support. Churches across the country were losing interest in inter-denominational efforts, and, after a period of waning support from the American Missionary Association, Berea had severed ties.

In spite of all this, Frost was optimistic about Berea’s future. He wrote in his 1893 Report, “The cordial and combined efforts of donors, trustees, faculty, alumni, students and citizens, are needed, but if they are resolutely put forth, we shall soon see Berea arise like Hercules from his cradle.”

And arise it did.

One of the leaders’ first efforts was to increase the size of the student body. Berea’s enrollment had been hovering at 350 to 400 students for a decade. With concentrated outreach efforts, the count increased to 486 students in the 1893-94 school year.

Frost also understood the imperative of gaining supporters and raising funds. In his 1894 Synopsis of President’s Report, he outlines an annual budget of $19,000. The endowment provided about $4,500 and $2,500 came from student fees. The remainder of $12,000 required donations.

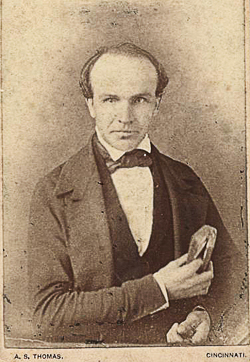

Rev. William E. Barton, an 1885 Berea graduate, was key to these improvements. He spent much of 1893 canvassing for students and funds in northern states. Frost spent the summer in eastern Kentucky doing the same.

This school was planted with signs and wonders. It has been watered by the prayers of God’s saints. It is a power in the world today; and it may be made an hundred fold greater.

President William G. Frost, 1893

Their efforts were aided by an initiative that reduced operating costs. An 1893 booklet titled, “Self Help is the Best Help,” outlined Berea’s first paid labor program. Less-skilled workers could earn up to one-third of their fees. Skilled students (e.g., book-binder, cook, dress-maker) could earn the majority of their expenses.

The tide began to turn quickly for the school. By the 1894-95 year, leaders saved and raised sufficient funds to begin paying off the debt.

With the immediate crisis averted, Frost began to look to the future. While the operating budget had relied on endowment interest since 1880, the fund had remained static at just over $100,000 for 12 years. Recognizing that two-thirds of annual costs depended upon contributions, Frost stated in his 1895 Synopsis of President’s Report that the next financial priority was “to secure a large addition to our endowment.”

These prescient decisions in the 1890s by the Berea College trustees became permanent elements of the school. The tuition-free guarantee. A network of supporters across the country. A paid student labor program. A significant endowment. All have continued to be defining and integral to the school’s identity through the next century plus.

In so doing, they made real Frost’s 1893 declaration: “This school was planted with signs and wonders,” he wrote. “It has been watered by the prayers of God’s saints. It is a power in the world today; and it may be made an hundred fold greater.”

Words can’t express how deadly I am excited to be connected with Berea college, this is nothing but a life saving and dreams come through decision that the board has taken to help not one but every human being that is willing to work your dream. Once again let me say a very big thank you to Berea college, I am following this page and I will always follow to be a living testimony to this great opportunity.